When Henry gets his check he’s gonna leave. Gonna buy a boat, name it Police Brutality. Said “that came to me in a dream, boys. And, shit, if I ain’t gonna do it.” Gonna move to Florida and hunt gator on the Okeechobee. Says he’s tired of fishing muskie here in east Kentucky. “Worst a muskie’ll do is bite your fingers off. That ain’t no challenge.” He wants to turn thirty-eight fishing with a shotgun on his new river rocket. He don’t want to see this place no more.

When Henry gets his check he’s gonna leave. Gonna buy a boat, name it Police Brutality. Said “that came to me in a dream, boys. And, shit, if I ain’t gonna do it.” Gonna move to Florida and hunt gator on the Okeechobee. Says he’s tired of fishing muskie here in east Kentucky. “Worst a muskie’ll do is bite your fingers off. That ain’t no challenge.” He wants to turn thirty-eight fishing with a shotgun on his new river rocket. He don’t want to see this place no more.

Or maybe he’ll stay. Every once in a while he’ll make a sale, something nice, a bedroom suite or one of those reclining sofas with the big mark-up and he’ll dance around the furniture store, finger pistols blasting at the dirty low lights. “How about that, boys? Guess we’ll stay open one more day. Guess I’m the saver, boys. Guess I’m the saver of everything.”

A year ago you were sitting in prison when you got his letter.

Hey Buddy,

Hope you’re doing ok in there and shit. I know nothing’s easy in that place where youre at but I believe you’lll be ok. I’m going to put a hundred dollars on your commissary so you can go ahead and maybe get you some more peanut butter cookies or whatever. I love you. You’re one of us even if you don’t claim it. I seen on the website you only got about four months left. Maybe when you get out you come back here and we’ll put you to work. Furniture moving ain’t fun but its a job. And at least you won’t have to worry about all that ex-convict shit. Hell, I’m pretty sure that the mayor of Hazard robbed a liquor store when he was younger. You just messed up in the fancy part of Kentucky.

Your old Buddy,

Henry Joe Deaton

They want him to stick around, the men that own the store, his father, his uncle. They’d never say it. But, sure, they need the help.

“Didn’t used to be like this,” they’d tell you. “Used to run three trucks a day with seven stops apiece. Wasn’t always this way.” The store has been in their family since the Second World War. Best place to buy a hutch or a dresser between Hyden and Dry Fork. But they’ve been ready to close it for a while now. Some days the only person to walk in the door is the mailman. You ever tried selling $2,000 mattresses in a town where the average income is lower than what you could expect to pay for a new roof ? You got to get creative.

“Listen, Ma’am, it might sound like a lot of money now, but I’m’a tell you a secret about the Ruffino pillow top. You wake up in the middle of the night, you roll right on over and you’re gonna have the same dream.”

They sing the same song every day. They repeat it because no one listens. The mines closed and the pills came and then everybody left. Eastern Kentucky ain’t much except roadkill and trampolines. At first everyone argues and blames. Then eventually no one comes into work on time. Lunch breaks become lunch days. After a while the employees just start drinking on the sales floor. Yesterday you were driving in to work listening to NPR. “Appalachia is at a critical juncture. With the end of the coal business, it’s time for us to ask ourselves what we want. Are we going to be a place that used to be? Are we going to be able to embrace the richness of our culture while still being able to move forward in a way that is meaningful and sustainable?” Fuck that, you think. Look around. This place seems like the exact opposite of a critical juncture.

When Henry got married he moved into the house where he grew up, the A-frame cedar in Backwoods. After the divorce he stayed. Camping out in the living room with his miniature freezer, his couch, his muskie trophies, his two hundred pound St. Bernard that he hasn’t named yet and his television perpetually dancing between Fox News and ESPN. The place smells like dogshit and childhood. After work sometimes you and he will share a beer on his couch and watch him cry. They called him Bullboy in high school. He once put Tim Couch out of a game on an end around blitz. Now he whimpers come that third beer and has nightmares in the daytime. “When I get my check, first thing I’m gonna do is drive past Layla’s house. Not past her house, cause I can’t. But I’m’a get as close as the law says I can and I’m’a honk my horn on my new car and she’s gonna look out her window and know it’s me.”

“What if she don’t look out the window.”

“Fuck her then.” He rattles the Purina bag and pours it on the floor. You know that tonight when you are walking home you’ll be picking bits of it out of your boots.

“The Bears fucking suck.” His fingers have swelled up past the point where he can remove his wedding ring and it lays across the remote purple and strangled.

“Yeah, they really do.”

“I should have fought back.”

“You couldn’t. You were handcuffed.”

“ The Cats need a point guard.”

“Somebody that can actually pass the ball.” You’re not sure if he’s even aware of the tears splattered across his face. He doesn’t wipe them off and for once he doesn’t apologize for them when he turns to look at you.

“What about that time when we was kids at the Black Gold festival. And your daddy locked the keys in his car three times on the same night?”

“Don’t remember all that,” you say and instruct.

Henry started drinking around ten in the morning that day that it happened. Brought a case of Bud Platinum with him on the john boat and when that ran out he switched to the little airplane bottles of apple vodka. Hillbilly hand warmers he called them. He took Layla out for lunch at McDonalds and started laying into her over damn near everything Started screaming about how he was a good man and she didn’t care about him. She only cared about her dead waterhead baby. Really didn’t care about anybody but herself. The manager at McDonald’s called the law and when the police came he just wouldn’t walk away. He told the cops about which of his body parts tasted the best. Invited them to try a mouthful.

They broke him open at the jail. Spilled parts of his face all over the cold stone floor. One police laughed at him and asked if he was going to fake a seizure like the last boy did. They chained to him to a chair and buried him with their fists and boots. They opened up a swamp of blood here, a clump of crackled cartilage there. The first time a nose breaks it makes a sound like a dog coughing. The second time it sounds like applause.

“You want to see The Lawyer,” one of them said. And then put the Taser in his eye. Halfway through the beating Henry’s face looked like an American flag. By the end it looked like a gasoline rainbow.

“You hit like a bitch,” Henry sobbed.

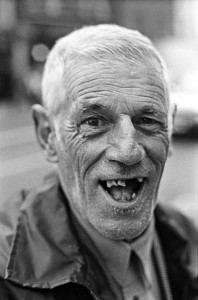

“Well, I guess that’s lucky for you then, boy.” The sear from the Taser burned a crater in Henry’s orbital bone. Gives him a walleyed overeager look so that now when customers come in the store they expect to be met with a sales athlete. A song and dance man ready to wax their tires and tell them about the gospel of E-Z finance. Maybe they’re surprised when he doesn’t say a word to them. Just turns back to his computer screen, waiting on five 0’clock.

Once, on a night you were so lonely (East Kentucky lonely; nothing-gonna-change-and-nothing-gonna-be-the-same-lonely) you heard about a woman who wrote a book where she spent one night with each and every one of her Facebook friends. It took her two years to write. She had almost eight hundred of them. You wanted to tell Henry, but he hates Facebook these days. Everybody with their posts about new houses and climate change. Everybody with their lives full of best intentions. Everybody so busy not being you.

“I ought to just delete my account,” he says. “Only reason I even look at it is to see the pictures of people’s fish.”

“You really should.”

“They think they’re all so fancy, don’t they? Let them try living down here. Let them try selling furniture with an African-born President who hates coal in the White House. Who hates working people. Who thinks the top of a mountain’s more important than the people who built this country.”

“You want to do a line?”

“Why, yeah.” The Oxy cuts grooves of moonlight into your brain. You stare at the family cemetery across the street from the furniture store. Farther into the ridgeline you can see the unsteady sway of the houses built into the mountain. They disappear in their ascension like clumsy old men on a final stagger towards heaven.

So, now Henry’s got two lawsuits pending. One against the Perry County police department and another against the jail. His lawyer is putting together a class action. Says there’s a big number coming. Henry’s money could back the bank off; keep the doors open. A horizon made of bruise. Or maybe send him down to the swamplands, another anonymous millionaire with a crazy story about how he made his money. The number can’t do both.

“Boys, they kept me in there for four days and didn’t feed me nothing ‘cept one bologna sandwich. They kept coming in there and giving me an Ibuprofen. I just acted like I ate it, but I stuck it in my pocket. They were trying to make my swelling go down and I weren’t having it. They knew they’d fucked up. They knew’d they’d gone too far. They was gonna try and pretty me up. But, I was gpnna come out of there looking every bit as bad as I was.”

Your own father had a habit of shooting television sets when he drank. “Caught one breaking into my house and another looking at the old lady,” was his standard joke whenever he was asked if it was true. He’d come home after work, crunched up from the day’s weight with nothing but his own misery and the screen to get him through the night. Then, finally, when he’d just heard too goddamn much that he couldn’t stand, the .38 would come out and he’d make that TV pay for its betrayal. You always knew when it was time to get out of the way because his speech would turn from slur to crackle. A slappy incomprehensible language that meant the same thing each time: “You think you’re better than me, don’t you?” Maybe it was the condescending way Ted Koppel read the news or something holier-than-thou about the way that fucking Howard Hessman pranced around the radio station, but some nights it was just easier for him to send a shell through the set than to turn the damn thing off. He’d feel bad about it the next day and he would always have a new one sitting on the coffee table before you got home. He only shot four of them that you can remember and every replacement was a slight improvement on the last. After the third time when he upgraded from a thirteen inch Sylvania to a twenty-six inch Sony, your mom whispered to you “maybe the Reds will lose tonight and your dad will shoot us up some cable.”

Imagine going to a stranger’s house every day for a year.

“Hello,” you’d say. “Do I look like my picture?” Would you all sit around and discuss the fact that you’re not just icons on a screen? Would you use the word ‘connection?’ As soon as you left wouldn’t your hosts say “well, that was just what we expected.” What’s the point of trying to prove we’re all in this together? Nothing could be farther from the truth.

Coffee table books are bullshit anyway, right? Like Henry said when he could still be funny, “that’s a waste of a perfectly good coffee table.” Besides, where’d she get the money to do all that? How’d she get the time? Seems like a lot of trouble to learn that all those people get embarrassed when they can’t spell embarrassed. Maybe they can’t love their kids the way the Like button does. That we’re all due a little more agony. Seems like a long way to go to find out what you already knew.

All the days are slow now. But today seems like it stopped at 10:30 to ask for directions. “Nope, he’s not in yet.” You tell the bank. You walk around outside just to kill some time. You see gravel. You see trees. You see skinny boys walking down the railroad tracks furtively eyeing the metal batteries on the store’s work trucks. Henry’s father walks outside and asks if you can step into his office. As you pass by the sales desk you hear Henry ask how old is the morning’s coffee?

“Can’t vote, yet. If that’s what you’re wanting to know.” They laugh and Henry returns to his story.

“You know what my first delivery ever was? Snake handling boy preacher down in Kingdom Come.”

“Shit,” his uncle says “the one on T.V.?”

“Yep. I was fourteen years old. He had rattlers and copperheads and all kinds of them in these little tupperware boxes all over his house. The boy I was delivering with took off running he got so scared. I had to do that whole job by myself. Afterwards, he shook my hand when I was done. I still remember how cold his hands were.”

“They keep them that way. Snakes are cold blooded, they fall asleep if a handler’s cold enough.”

“Yep.” They pass back and forth a bottle of something brown, murky and hopeful.

“You remember your first one daddy?” Henry’s father stops on his slow trot to the office. Decades of packing pianos and dishwashers have given his knees a tentative buck as he moves. Almost as if they were saying, “can we talk about this?” before he takes another step.

“I was in Glowmar and we was up in the holler. And we was near the head of the holler and there was these people there and they had bought a living room. Well, you could tell that they had never really spent much time out of the holler. So, we bring it on their house and of course they had them a dirt floor, course back then about everyone around here had them a dirt floor.”

“I remember dirt floors in Hellfercertain.”

“I’m telling a story, boy.”

“Sorry.”

“It’s ok. Anyway, there was this girl setting out on a tire swing by the house. She couldn’t have been more’n nine or ten and she asks me to come on over. And she says ‘I got a secret, but you can’t tell nobody. And then she whispers to me ‘I shit little white worms.’” When they are done laughing Henry asks for another cigarette.

“That wasn’t really your first delivery was it, Daddy?”

“No, honey. But it was about the only one I can still remember.” You step in the office and you shut the door.

The only other thing you can remember your dad shooting besides televisions was himself in the forehead on a Fourth of July weekend just after he gave you twenty dollars and asked you to make a third (and in your mind unnecessary) ice run. Your joke, because you inherit these things from your father and because you are not particularly clever is, “Maybe he thought he was on TV.” That’s why Henry’s daddy called you into his office today. He wants your expertise, your trained eye. They say Henry has been having trouble since the beating. He can’t eat. He follows his ex-wife everywhere. They are worried about their boy. And they are worried about their money.

“The other night he got into a fight with some black boys in Backwoods. Started calling them ‘niggers’ and such. He ain’t racist. I didn’t raise none of my boys to be like that. It was like he was looking to get beat. Your daddy ever do something like that?”

“No sir. He let the beating come to him.” Mr. Deaton stumps his cigarette on the desk next to reams of unpaid bills and carpentry magazines. Above his desk you see an old photograph of you and Henry when you were both in the first grade. There’s you, huddling and shy. There’s Henry flexing his muscles like Hulk Hogan. There’s yesterday in a Polaroid smelling like cigarettes and debt. “I’ll tell you something, I think Henry is gonna kill himself before he gets that money. And if he don’t, I damn sure know he’ll kill himself with it afterwards.”

Some part of you wants to tell him not to worry. To tell them there’s a name for what Henry’s got. That doctors study it. And that doctors can cure it. But, then you see your father with that Sylvania. Listening to the whole world laugh at him in a language all his own. And then you see Henry staring into the computer. Figuring out maybe he’s just part of the problem. Just wishing someone somewhere would put up a picture of a fish and make him happy again.

Towards the end, what was your daddy like?”

“He slept a lot. I remember that.”

“Yeah, Henry does that too.” Yeah, there’s a name for what Henry’s got. It just ain’t the one you wish it was.

At 4:18 the police car pulls into the driveway. Whoever’s inside of it lets the engine run for a solid ten minutes before it turns off. It’s only you and Henry left in the store. Henry is drunk. You are worse.

“Is that one of them,” you whisper.

“They’re all one of them.”

“They did this last week, too.” Through the dark tinted glass you can almost make out the officer’s face: twenty-five, clean, sagging. Someone has told him this would be intimidating, and maybe it would be if the cop didn’t keep compulsively scratching his ear.

“The fuck is going on with his ear?”

“Yeah, Officer Napier, we’re gonna need you to sit in the parking lot and stare at the boy who’s suing us. Do you copy?”

“Roger that Sergeant. Will you need my serious face or my extra scary face? Over and out?” Behind the squad car you can see a mountain that looks like a mask. And a parade of trucks with the same exact bumper sticker: If you don’t like coal don’t use electricity. Your daily reminder that to live is to be hypocritical.

“Come on in,” Henry calls out. “Come on in, buddy and make yourself at home.”

No one moves.

“We got all kinds of good deals. Come on in. Come on in and leave that fucking gun and badge inside your car. But bring your Taser. Make sure you bring me The Lawyer. I’m’a fuck you up. I’m’a show you just who you fucked with.” You want to tell Henry to stop screaming. That he sounds like an idiot. But then you realize it’s not Henry’s voice. It’s yours. And it is you who is stumbling through the sofa tables and the dinette suites across the shag carpet. It’s you who’s red-faced and hollering at the blue and white. And it’s you who Henry wrestles to the ground. He’s so strong. It’s like a building collapsing on you. And then you are laying underneath the Saver next to the front door of the furniture store. And the “Someone is Here” bell is going off incessantly because he has tackled you in the alarm zone. And you are smelling insecticide and old cigarette butts. And he is yelling and whispering at the same time.

“You will not fuck my money up. I don’t give a fuck. You try me I will kill you.”

You want to fight back. You push against his chest but you may as well be attempting to lift a train off your body. And that’s when you remember what people used to say about Henry Joe Deaton, before the police came and made a doorstop out of him: That boy was so tough, he’d fight a buzz saw.

“You think I’m playing with you? I am not playing with you. I’m’a let you up and if you take one step out that door I will take you outside and I will drown you in the river. I played at that riverbank my whole life. You want to hear how many boys I seen die in that river? I know just how many bubbles come up before a boy drowns. I will sit on the edge of that river and I will count the bubbles. Understand?”

Outside the cop is laughing himself to tears. He’s hunching over the steering wheel collapsing with cackles. Finally he hits his misery lights, burning up the early evening darkness with the blue and red bulbs.

“I got plans for that money,” Henry says into the back of your neck as the two of you watch the police dragon tail through the parking lot and disappear back into the town.

The lawyer called again. It’s going to be at least another year before the settlement is reached. Maybe two. Everybody’s waiting.

Isaac Boone Davis is a manual laborer in the coal economy. Tangentially he is also a drifter, a thief, a personal trainer and singer of sad songs. He is the dude on the left. He is currently half-assing a novel about the same characters who appear in The Meantime. His work can be found at Writethis.com, Smokelong Quarterly, Fiction 365, P.I.F., Efiction, The Blue Lake Review, Jersey Devil Press, Two Hawks Quarterly, The Southern Pacific Review, Black Heart Magazine, The Ampersand Review and others. He can be reached at isaacboonedavis@gmail.com

–Background Art by Alphan Yýlmazmaden

–Foreground Art by Seamus Travers

Sneakers Store | Nike nike air max paris 1 patch 2017 , Sneakers , Ietp STORE