There was an evening when my brother and I were pulled by our mother from some game of our imaginations into the living room where my father sat wearily on the couch. He had returned from Rochester, New York, where his parents lived, to Richmond, Virginia, which we called our home. He traveled often, and in this way, nothing seemed out of the ordinary, though even at eight, I do recall that he was, for lack of a better word, muted that evening. Not in voice, but in spirit. His voice he used carefully, calmly, with the gentleness that would forever, more than anything else, define him to me. His father, my grandfather, had died. The immediate result of sharing the quiet grief of his body with the bodies of his body was barometric. The air grew heavy. I did not understand it then.

I suppose, in part, I can understand it now.

Gene Bartlett’s passing must have taken a great toll on my father, David. Perhaps insufficient in my development, I was still lacking in understanding mortality. In my short life, every night had always beckoned a new morning, and in years when all days existed to announce my next birthday celebration, I was certainly the center of a universalist claim. If nothing else, Sunday School had already taught me about the reality of an empty tomb and the even more magnificent gospel of Saturday morning cartoons declared that no amount of TNT, falling boulders, or backfire of ill intent would take Wile E. Coyote from this animated earth.

I did understand that there was tragedy in losing my grandfather. By this I mean I understood that many things would change and none for the better and all permanent. My grandfather kept chocolates hidden for his grandchildren in his closet. He laughed at songs that we sang about him, and the way that he outdressed any Hollywood royalty. I always rushed first to him to be lifted and hugged and held outside a Massachusetts house that the extended family would rent for a week in the summer. These things, and these all things of great value, were gone. But I had no sense that I was changed, much less that I in my own way was lost. I recall my father telling us of his father’s loss in the same way that I recall watching the Challenger explode. The earth below my feet reverberated, but I did not yet know the language of injustice.

My father’s passing left bare my pedestal, but to most others it left empty a pulpit. He had pronounced on many a Sunday not just the words, but the truth of his beloved Paul. Nothing, not life nor death nor anything else in all creation, can separate us from the love of God in Christ Jesus our Lord. His skill brought him to the academy and made him professor of what he faithfully professed. Thousands learned from him. Thousands now, myself included, mimic him. Especially that booming voice going nearly silent at points of emphasis of grace. Especially a steady hand raised above his head in proclamation. David Bartlett, by virtue of being David Bartlett, inherited a great extended family and demanded from his private life a powerful public theology. Could a handshake, embrace, wink, roaring laugh be small signs of sacredness? Could meals at his table, of course also the table of my mother, be sacrament?

These are questions for another time.

In my kindergarten classroom each child was given an empty book in which we could draw or write anything that we deemed worthy of sharing with our families. I drew a purple, oval-shaped racetrack with a number of crudely designed but brightly colored race cars, each marked by a number. Two cars reached the end of the track while the rest were stifled behind. As I wasn’t yet able to write well, my teacher penned the words that I requested. “41 and 45 are the winners.”

At the time of this artistic endeavor, my mother was forty-one years old. My father was forty-five.

It wouldn’t be until much later that I could ask important biographical questions. There was a certainty, however, during my young elementary years that the answers my father gave to the simplest of questions were the standards of goodness, and thus my childhood goals. My father’s answer became the right answer to every question into perpetuity. “How tall are you, Dad?” “Six feet tall,” and I would aspire to be six feet tall. “Dad, how much do you weigh?” “One hundred and sixty pounds,” and this was the ideal weight. “How old are you?” “Forty-five”…and it wasn’t until the answer was “Seventy-six” and would not be “Seventy-seven” that any answer was profane.

My earliest recollections of the life of my father and our lives together convinced me repeatedly of the soft-spoken nobility of the role. “Father” meant these things and many more, none the definitive good, but all strikingly invaluable: playing catch in the yard, enthusiastically applauding living room reenactments of The Music Man, pancakes made in the shape of a “B” for Benjamin or a “J” for Jonah, books read to us in bed—Roald Dahl, Shel Silverstein and more—his own original stories of Marmaduke the mouse who loved marmalade, lullabies from West Side Story, trips to ice cream shops, left field bleacher seats in the hot sun of the Oakland Coliseum when Rickey stole second and then third, drives up and down the California coast making many stops to investigate rocky beach tidepools, summer days at Knotts Berry Farm, rainy day afternoons with the animatronic dinosaurs at the Lawrence Hall of Science, saying “Goodbye” to his boys, but never walking away until we were safely inside the doors of the school. Small becomes great in grief-filled retrospection.

When his sons awkwardly grew into teenagers we, like all teenagers, found plenty of extracurricular activities with which to occupy our time. Some of these included Dad, but not all. He understandably didn’t have much interest in Final Fantasy video games or basketball showdowns with friends charging the hoop in his driveway, the ball more than occasionally hitting the sides of the leased Ford Taurus. He did, admirably, accompany one son (this one) to WrestleMania XI. But time once dedicated to keeping a close eye on young children was suddenly again his own, and he could claim this space to try on a new hat which was a baseball cap, part of a uniform in tandem with a lawn chair and binoculars. Planting himself on the lawn before the pond that ran through our backyard, now in Connecticut, he became a bird-watcher.

Dad carefully kept the name of every species spotted in a book by the Audubon Society. Oriole, Woodpecker, Wood Duck, Robin, Blue Heron, Cardinal, Blue Jay, Chickadee, Kingfisher. He was not alone in this hobby but often accompanied by our dog, John, named by Dad’s perhaps someday creative children. John was half Beagle and half German Shepherd. He had an indelible appetite, and by virtue of this appetite, his famed heftiness. Many weekday mornings I would look out the living room window, which faced our backyard, and there would be the familiar party facing away—my father with The New York Times and a cup of coffee, John with his ever-present and cartoonish contentedness, and the two Mallard Ducks with whom they had both become fairly close. This would have made a great photograph, but a memory will have to suffice.

John, like all good dogs, was not just a footnote in the family history, but a vital member of the supporting cast. We chose John, a puppy with a black back and a peppered belly, from amidst a clamoring crowd of pure white littermates. And this tiny outcast became the source of great joys. He ran the width of every yard. He was our lookout, albeit quite friendly after just a few hard barks. He put smiles on all faces. He helped to dry all tears. We all handed John scraps of our dinner when he pushed against our legs under the kitchen table. Only once his hunger outsized his stomach, and he became terribly sick, but only for a short time, after inhaling a wheel of brie. He hated thunderstorms and those loud claps made him chew at his wooden doghouses in anxiety or crash through screen doors with the hope that on the other side was some tranquility. First, he traversed the California hills. Then he crossed the country in a crate stuffed within our Volkswagen van. John pranced around the camps where we made our stops, chewing at unidentified pieces of nature. He preceded Val, who preceded Folly, as the third, fourth, and fifth sons. He had adventures. And while we were distracted by the adventures of John, we passed over what the totality of the adventures meant—he was growing old.

One afternoon my father was sitting in his chair in the backyard, facing the pond, looking for new birds to count, when John, per usual, lay down at his side. John never stood back up. His brown eyes that widened as my father attempted to lift him could not possibly understand what was happening. John’s aging body was too heavy for John’s aging legs. He didn’t whimper. He just remained in a state of unknowing as my father took a blanket from his bed, gently and sorrowfully rolled his companion atop it, and dragged him, by way of the front garage door, inside to some comfort where we all surrounded him. And, despite hope against hope, we trusted our father when he told us that it was time. He went by himself with John to the veterinarian. Eyes closed and heartbeat stopped, and although we all still had one another, we were all now profoundly alone.

For some reason, between the second grade and the final years of college, I could never divorce education from anxiety. In those earliest years I was exposed to a wickedness of power that, by virtue of height and age, school employees held over me. To this day I know that they shamed me. Perhaps more so now than then, I understand that it was they, not I, who had no rightful place in those hallways and classrooms. Then I whimpered at the breakfast table. I feigned sickness as best I knew how—holding thermometers near light bulbs, bending over and hugging my stomach, groaning because of the fictional pain in my head or relentless nausea. Sometimes my parents would go along with the charade. I would end up in my father’s office with pencils and paper, illustrating stories about animals who also happened to be professional wrestlers. Sometimes I would need to be pushed, by word not action, onto the school bus with the friends outnumbered by the bullies, and the bus driver who turned his eyes from the prepubescent struggles. I think now, knowing a father who rushed to my room when I yelled for escape from the plots of nightmares, who played guessing games inside doctor’s offices to create playful distractions from routine yet terrible exams, who drove five hundred miles through the night to be at my bedside when I awoke at the hospital after seizures had captured my body, spirit, and soul—that this paternal insistence to face my fears likely pained him then more than it pained me.

The trend of an almost daily reenactment of The Great Escape continued into middle school. High school brought some relief as I accrued a large, rowdy, and ridiculous group of friends. After graduation these friends all attended local colleges, while I traveled enough of a distance to soon enough feel at night the snap of ties being broken. I missed them. And my mother. And my father. And a comfort of familiarity that would be lost, and really to this day never recovered. I thought my father would call me home when he heard the tears flow through miles and miles of phone lines. He insisted that I stick it out. I did, and I am glad that I did. But the insistence did feel strange. A lesson learned again and again and again, and finally so terribly—the inevitability of change.

If there was to be a specter of one more member of the family—beyond father, mother, two sons, and John, we welcomed his friend Shakespeare into the home. Car rides to New Haven or train rides to New York City called us as witnesses to the work of the Bard: Macbeth, The Taming of the Shrew, The Tempest. As a result of these evenings, for a brief moment in time, I believed foolishly (and not in the sense of Shakespeare’s surprisingly wise fool) that the theater was calling my name. Appropriately during my freshman year, I was cast in a low-budget hodgepodge called Shakespeare’s Window, a host of scenes from a number of my adopted beloved’s works. I was assigned the role of “Gravedigger One” in Hamlet. And fond memories remain of sitting on the living room couch running through lines with my father, who took on the role of my counterpart, “Gravedigger Two.”

During one of those last few days when air became breath, and breath became speech, and speech became hope, I asked my father for the title of his favorite Shakespeare work. “Hamlet,” he told me with a dry mouth. My mother gave him water by way of a sponge at the tip of a plastic straw.

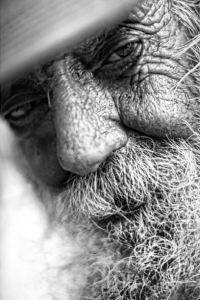

If Shakespeare wrote of the truth in Hamlet, we orphaned children know, the villain is not Uncle Claudius but the all-powerful God who looms silently above Denmark. Ophelia is drowned, Gertrude gone by the poisoned cup, and Laertes lost by the poisoned tip of the sword. All sorrowful but none tragic. This criminal we Christians call Love, fell short of that title— “Here,” he said, “is the inner but not the outer. This is more than enough. The spirit but not the body. Be thankful (Alleluia! Alleluia!) for what you get.” God sends Hamlet the spirit of his father to warn, but not to mourn. The spirit, but not the body. A mockery of a miracle. Because here is what this son, Hamlet, and here is what this son, Jonah Kenyon, truly need to redeem the suffering. The scratch of his beard across my cheek, the strong, reassuring hand around my younger shoulders, the feeling of his stomach against my elbow as we struggle into a tight couch on a Christmas morning. I miss the body, even the broken one. I miss the man.

Here I will describe the power of my father against the sights that he took me to see during summer vacations. Taller than the redwood trees in Muir Woods, deeper than the Grand Canyon, more powerful than the crushing blow of Niagara Falls, more defiant than Christ of reality. For this is what seminary tells you of reality. We are a broken people. We are a lost people. We are separated and will be separated from the presence of our God until the appearance of a Kingdom. If for no other reason than keeping me afloat as I learned to swim in the Finger Lakes…if for no other reason than the support of a dream of a punk rock band…if for no other reason than a poem written for my mother on the occasion of every anniversary…I am all but certain that he rubbed shoulders with the divine. And the divine, attempting to keep distance and unaware of his incredible volume, made him laugh.

I am left to wonder if, when my father sat beside my mother in the pews to hear me preach, he could sense that the conviction of my faith was a pitiful fraction of his own. It still is and, by virtue of his absence now, it likely forever will be.

I was enthralled by his body when he mowed the lawn. We were both to excel at our love of sports, but never at our participation in them. My father tried to compliment me when I played in a baseball clinic on a field behind my elementary school. He bought me Big League Chew from an ice cream truck and insisted that had my line drive not been caught by the pitcher, then it would have certainly been a double. Not to mention, he would add, my athletic prowess was a bit better than his own. But from the kitchen window I saw him push that heavy machine, yellow stains on his undershirt right below his armpits, half the blades of grass sucked into the lawnmower’s bag and the other half shooting upward into the air. Back and forth, evening the chaos of our territory, a force to be reckoned with. He would then come inside and pour a glass of iced tea or lemonade, assess the contents of the refrigerator, and breathe a deep breath. No fear then, I suppose, that any of these would be the last.

On many Fourth of July nights, and many of these nights occurring while his father was still alive, we stood as a family on the edge of Green Lake in Wisconsin and watched the fireworks explode in the air. Earlier in the day we had marched in a parade as Yankee Doodle Dandy. The night before, we sat around a campfire and sang as we toasted marshmallows. Sticky and sweet and just a small reminder that life was messy, but life was good.

On one Fourth of July, now one year ago, I stood in his hospital room, his body frightfully still behind me, save the uncontrollable movements of one hand, and looked out the window, fireworks exploding above Hyde Park in Chicago, where my parents met, where I was born, where I was born into this gift of a life, gift of a love, gift of a parent who even now, without the ability to speak, resounded with adoration of his grieving creations. One surgery would come the next day. We didn’t know that this would be the first of a few, and a few too many. The fireworks done, holding his hand, my head on his chest, I watched the A’s hit a walk-off home run in the bottom of the ninth. I knew there was symbolism in this victory that he could not witness. I can’t yet tell what it was.

I doubt the significance of the timeline, as the result, despite length or depth, remained the same. He and my mother were staying at the home of friends in Chicago. He was teaching a summer course on apologetic preaching at the University’s Divinity School. Appropriate, as the Gospel still has yet to apologize. Perhaps the bags were too heavy or his balance too awry, but whatever it was, he fell down a flight of stairs and battered the brain that for so long had mesmerized so many. He spent many weeks at the hospital in Chicago. Then he was flown to a Connecticut clinic, where, in a small, private room, air became breath, and breath became speech, and speech became hope. I rolled his wheelchair outside, where we took in the sun like we used to do in the left-field bleachers at the Oakland Coliseum. He was beautiful in the sun. Then hope took on the same fate as Hamlet. Next was a room at Yale New Haven Hospital. Next hospice at his home. My father, David Bartlett, passed away on the morning of October 12, 2017.

I have a favorite photograph of my father, despite the somewhat criminal fact that one cannot see his face. He is standing robed and head bowed in a Presbyterian church in Texas. I am to his left and holding in front of me the hands of my soon-to-be-wife. This is our wedding. He is officiating by law of land and liturgy. He is uniting the two halves, one a body of his own body, as a new body. Outside the edge of the photograph is his elder son, the best man. Not far away in the front pew is his beloved wife. One realizes, looking at this photograph, if one is willing to look beyond the moment to the eternal, that finally this day, as much as anyone else’s, was his. Present to see the love that he had instilled now manifest itself anew. Present to see the love divine now love excelling. Present, since now we know he won’t be forever, and accounted for as our debt to the Great Taker made just, only by the grace of the gift given.

Jonah Smith–Bartlett is an ordained American Baptist minister and received a master of arts and theology at Union Presbyterian Seminary. He also received a master of divinity from Yale Divinity School. He loves to write about small-city America and examine how deceptively simple moments in the nation’s history can shatter lives, embolden relationships, and transform the face of a community forever. In his spare time, I play the tin whistle and sing in an Irish band. His work was recently published in The Delmarva Review, Entropy Magazine, Euphony Journal, Forge, Free State Review, Gemini Magazine, Glint Literary Journal, Longshot Island, pamplemousse, Sliver of Stone, Valparaiso Fiction Review, Verdad, The Westchester Review, Whistling Shade, and 10,000 Tons of Black Ink.

–Art by J. F. Chow — Artist Profile