Elaine Neil Orr: A Search for Home

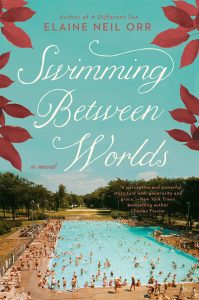

Elaine Neil Orr grew up in two worlds: Nigeria, her birth place, and the United States, the country stamped on her passport. Swimming Between Worlds is Orr’s third book to address her search for home and identity. Gods of Noonday: A White Girl’s African Life (University of Virginia Press 2003), is a memoir that chronicles her childhood as the daughter of medical missionaries during the 1950s-1960s. In the foreword Orr writes, “Nigeria is the place of my hidden self that is truer than my public self. It is the country of my heart.” Her first novel A Different Sun (Berkley 2013) tracks the journey of Emma Bowman, an American missionary wife who leaves her comfortable life on a Georgia plantation to travel to West Africa in 1853. Her second novel, Swimming Between Worlds (Berkley 2018) follows Tacker Hart, a young architect, from his work assignment in West Africa back to his hometown of Winston-Salem, North Carolina, during the Civil Rights Movement from 1959-1960.

I met Elaine when she was a small child living with her family during a one-year furlough in North Carolina. Our parents were part of a network of missionaries who visited in each other’s homes and worked and worshipped together. Many years later, Elaine and I reconnected as adults at a writers’ conference where she was a featured speaker. During a break, we swapped stories about what it was like growing up as MK’s (missionary kids). The themes of Orr’s books are familiar to me: searching for home, maintaining a dual (and sometimes secret) identity, and being an outsider in both worlds.

Beth Copeland: In Swimming Between Worlds, you write, “People who have lived deeply in two countries always bear the awareness of both, even in their physical movement, like a twin carries his second self even when separated.” How has being raised in Nigeria and the United States influenced your writing?

Beth Copeland: In Swimming Between Worlds, you write, “People who have lived deeply in two countries always bear the awareness of both, even in their physical movement, like a twin carries his second self even when separated.” How has being raised in Nigeria and the United States influenced your writing?

Elaine Neil Orr: No other single reality has influenced it more. One phenomenon of growing up outside of one’s passport country (except for furloughs), is that early on, one isn’t sure where one belongs. On the other hand, I latched on to southwestern Nigeria like the native-born child that I was. (In traditional Nigerian belief, one belongs to the country of birth.) I wrote two books set primarily in Nigeria. I thought in writing SBW that I was writing a less autobiographical book, and in many ways it is. And yet since its publication, I’ve realized that even in this second novel, I am searching for home.

My family lived in Winston-Salem one year on a furlough in the very house that Tacker occupies. I thought I was setting the novel in Winston simply because it’s an American city I love and have memory of. But in fact, Tacker is searching for home throughout the novel, and thus I am too, vicariously re-enacting my own lifelong search. Another phenomenon of being what is sometimes called a “global nomad” or “third culture kid” is that one always carries at least two global points of view. I grew up primarily in Nigeria but was also shaped by three furlough years in the American South. And I’ve lived my adult life in the American South. When I hear about a drop in oil prices, I think about the Nigerian economy not what gas will cost me at the pump. When I hear about global warming, I think about the anticipated effects in southern Africa before I think about the North Carolina coast. A third phenomenon for me–and this one can’t be underestimated, is that my spiritual life is profoundly influenced by Yoruba culture. I explore that influence at length in Gods of Noonday but it comes in to play in SBW as well. Tacker’s baptism in the Osun parallels my self-baptism in the Ethiope River when I was eight years old living in Eku, Nigeria. I had not been baptized into the Baptist Church yet. I chose a self-baptism in a river that was devoted to a female divinity in the religious sensibility of the region. Of course I am also deeply moved by the story of Jesus and the parables, many of which I memorized as a girl, and the Sermon on the Mount.

So all of this was swirling in me at an early age, along with the regional arts that claimed the devotion of my eyes: indigo cloth, beautiful carved veranda posts, enormous hand-made clay pots. And the drumming through the night–that accompanied me to sleep. It is all in me, clamoring for attention. I write out of this overflow of powerful feeling (to use a phrase from William Wordsworth).

Beth Copeland: Duality is reflected in your use of two protagonists: Tacker Hart, a young white man who travels to Nigeria to work on an architectural project, and Kate Monroe, a young white woman from an aristocratic Southern family. Was your choice to use two protagonists deliberate or did it surface intuitively?

Elaine Neil Orr: It was deliberate. But I also early on conjured another significant character, Gaines Townson, an African-American man who crosses paths with Kate and Tacker in the novel’s first chapters and ultimately who upturns their world. From the beginning, I discerned that Tacker would be the typical white American town hero. He would go to Nigeria on a good will project and get sacked and sent home. I needed this experience in order for him to be a likely candidate for persuasion when Gaines comes along. I wanted to hold the political arc of the Civil Rights Movement in tension with a romantic arc, so Kate appeared. At first she was rather slender, by which I mean she didn’t have nearly as many pages. But that was unsatisfying because she wasn’t a complex enough character to hold Tacker’s attention. In the end, she had as much narrative space as Tacker.

In contemplating your question, what I find satisfying to note is that Tacker, the male character, is more like me—he goes to Nigeria, gains another point of view, and has to find a way to bring them together if he can. Kate is not like me at all. I never belonged to the upper middle class of white America—far from it. We “lived on the edge of poverty” as my mother liked to say about missionary salaries. I never inherited a house. My parents lived into old age. So perhaps Tacker is my Nigerian self and Kate is the American girl I tried to become—not so much in terms of wealth but in terms of having a place, a home, a shelter. Though like me, hers is not as stable as it looks. Throughout the novel, she is working hard to make certain she doesn’t lose her place. In the end, of course, her place changes. We can’t talk too much about the end!

Beth Copeland: Duality is also reflected in the racial injustice present in colonial Africa and post-slavery America. As a writer, you skillfully travel back and forth between Nigeria and the United States, but the transitions are challenging for Tacker Hart. Why is his return to Winston-Salem, North Carolina, so difficult? Is he experiencing reverse culture shock?

Elaine Neil Orr: Yes it is, exactly. When my husband and I first married, my parents paid for us to visit them in Nigeria. We were only there a month but we toured all the places where I had grown up. In my parents’ words, “your marriage will never last if your husband doesn’t see how and where you grew up.” Maybe they were right. We’ve been married forty-two years! When we returned to the U.S., my husband had culture shock, much greater than mine at the time because it was his first time out of the U.S. He was stunned to return to the excesses of American malls (why miles and miles of men’s shirts in a department store?) and what might be called the “second remove” from reality that much American life implies. In Nigeria, we saw the living chicken we would later eat. We saw the garden where the vegetables were grown that we would enjoy. We met the seamstress who would sew Nigerian clothes for us. Tacker encounters similar ways of life in Nigeria when women vendors sell him food they’ve made in their kitchens and brought to the market. No hamburger joints there. The intimacy he feels with the Nigerian men on his project is an extension of this less removed way of living. Growing up, I felt Nigeria was a first reality and the U.S. was a television show.

I thank my intuition for making Tacker a privileged, beloved town hero because when he comes back and sees Winston-Salem with new eyes, he has some choices to make. And choosing in one direction means he risks losing a great deal.

Beth Copeland: You use third person limited point of view in Swimming Between Worlds as well as in your first novel A Different Sun. Why did you choose to use that point of view as opposed to first person or third person omniscient?

Elaine Neil Orr: I would love to use first person and I may in my next novel. But I wanted two narrators in this novel to create greater tension. Maybe I’ll always need two narrators for all the reasons you are bringing to light—the dual nature of my life and mind. Honestly, I’m not sure I can handle third person omniscient. It’s not yet in my bag of tricks. Isn’t it awfully hard?

Beth Copeland: In addition to Tacker and Kate, black characters from the United States and Nigeria—Gaines, Frances, Valentine, Samuel, Joshua, Chukwu—play an essential role in your novel. Cultural and racial appropriation has become an important topic in literary discussions. In Swimming Between Worlds, the black characters have a voice, but you don’t speak for them. How did you avoid writing about them in a way that would be exploitative or disingenuous?

Elaine Neil Orr: A good question. In my first novel, A Different Sun, I included a Yoruba man from 1850 as a point of view character. Growing up among Yoruba men in our homes and all around us, I felt a cultural tie with ways of thinking that might make such a character available for me. I consciously decided not to give Gaines’s point of view. An African-American man’s thinking in 1959 was not a territory I knew enough about to enter. I did everything I could to make him a complex character with a particular way of speaking and carrying himself, a personal style. If I succeeded, I give credit to Toni Morrison in particular because I have studied her male characters for years. In a crucial scene, I don’t have Gaines tell the story of Emmett Till. I have Tacker remember hearing him tell it. These were conscious choices to place the narrative voice where it might hear Gaines’s witness and then try to figure out what to do with it. I try to give dignity to all of my characters, even Joshua, the Nigerian man largely responsible for Tacker’s ouster from the prestigious project that won him entry into Nigeria.

I have stories to tell because of where I have been and how I have lived my life. I respect the need to be vigilant. The Civil Rights Movement invites a plethora of stories and we still need to be telling those stories.

Beth Copeland: Swimming Between Worlds takes place during a period when you were a young child. It’s set in Nigeria, where you were raised, and in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, where you lived for a year. Please discuss the research you did in preparation for writing this book.

Elaine Neil Orr: For my memoir, Gods of Noonday, I did a huge amount of research, reading old copies of the Nigerian national newspaper of the period, reading books by Nigerian authors, mission histories, excavating family memories, and going through old family slides. I had made myself well acquainted with the colonial period through the end of the Nigerian Civil War. So I didn’t have to do much new research about the country. I did interview a Nigerian friend who attended the University of Ibadan in the ’60s to learn about the political mood on campus. As a girl, I had passed by that campus many times. And I knew the art of Suzanne Wenger, the historical woman on whom Anna Becker is based. I visited the sacred garden of Osun many times.

In Winston-Salem, I located the town historian, Fam Brownlee, who was a fount of information. He’s really a living history, because he attended Reynolds High and had friends in the West End neighborhood and knew all about the city going way back. I also went to the New Winston Museum where I located more of the African-American perspective on the sit-ins. And I went to the Civil Rights Museum in the Woolworth’s in Greensboro where the most famous sit-in occurred. My favorite form of research was spending many days and nights in Winston, in West End, walking the streets, following Peter’s Creek, recalling my family’s year there, sinking my fingers into the soil, and falling in love with the place.

Beth Copeland: Your first book Gods of Noonday is a memoir of your childhood in Nigeria. How did you make the transition from writing creative nonfiction to fiction? Does fiction enable you to explore topics you couldn’t write about in a memoir?

Elaine Neil Orr: Sheer will power is how I made the transition from CNF to fiction. That and studying other writers, particularly great novelists, beginning with Henry James and Virginia Woolf but also Cormac McCarthy and Lee Smith and Toni Morrison. A friend of mine who had begun writing short stories when I was writing my memoir told me that fiction allowed her to “take the roof off the building.” I can’t say exactly what she meant but the image suggested to me that the sky’s the limit. I liked that idea. Even though I’m writing historical fiction and respect what actually occurred (as far as we can know), I’m also using characters of my own making, creating a recognizable world but also a world that only I could bring into being. How many people are bringing Nigeria and North Carolina together in the same fictional world? Fiction is beautiful dreaming. I’ve started on the next novel.

Elaine Neil Orr was born in Nigeria and lived in that country during colonialism, independence, early nationhood, and civil war. Her visits to the U.S. were brief until she was sent with a one-way ticket to the U.S. at age sixteen. In addition to two scholarly books, she is the author of a memoir, Gods of Noonday (UVaPress, 2003), and two novels, A Different Sun and Swimming Between Worlds (Berkley/Penguin/Random House, 2013, 2018). She has received grants from the National Humanities Center and the North Carolina Arts Council and is a frequent fellow at the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts. In 2016, she was Kathryn Stripling Byer writer in residence at Wesleyan College, Macon, Georgia. She is a Professor of literature at North Carolina State University and teaches in the Spalding University brief-residency MFA in writing in Louisville, Kentucky.

Beth Copeland is the author of three full-length poetry books: Blue Honey, recipient of the 2017 Dogfish Head Poetry Prize (The Broadkill River Press 2017); Transcendental Telemarketer (BlazeVOX books 2012); and Traveling through Glass, recipient of the 1999 Bright Hill Press Poetry Book Award (Bright Hill Press 2000). Her poems have been published in numerous literary magazines and anthologies and have been featured on international poetry websites. She has been profiled as poet of the week on the PBS NewsHour website. Currently, Beth serves as Gilbert-Chappell Distinguished Poet for the central region of North Carolina and teaches creative writing at St. Andrews University.

–Art by Placeholder