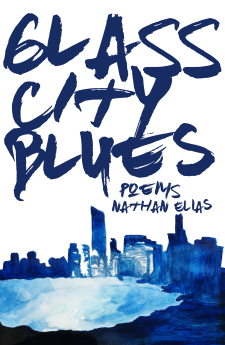

Can you tell us about Glass City Blues? What were your inspirations for it?

Can you tell us about Glass City Blues? What were your inspirations for it?

I’ve been carrying around the title, Glass City Blues, since approximately 2008. I had written many horrible poems around this time, the cause of which was too much exposure to the beat writers. I admit that Jack Kerouac was one of my gateway drugs into the writing life, though my tastes have drastically evolved since the early 2000s. Around this time I had lived in a place in Toledo, Ohio, where I’m from, also known as the Glass City, called The Collingwood Arts Center. The Collingwood was a place where artists and writers lived, a beautiful and gothic-style building. I remember I didn’t even have a bathroom in the unit where I lived, and the community kitchen was in the basement. However, what The Collingwood lacked in amenities it made up for in culture and heart. Two poets hosted an open mic that was held there, and it was easy for me to come out of my room and just walk down the stairs to the readings.

I had just dealt with the loss of my mother, and I think I was in desperate need of an avenue to express myself. The many open mics in Toledo provided this outlet. I wrote a chapbook of poems and started reading them any chance I got. I printed these awful, expressive, mostly-intelligible poems myself and stapled them into a booklet. I’d hand them out whenever I was a featured reader. I even submitted this manuscript to be considered for the Edward Shapiro Senior Writing Scholarship at my school, which I won. I knew, though, that deep down the poems weren’t my best work. It was not long after when I did an independent study at The University of Toledo learning to use a letterpress. I compiled an anthology of Toledo poets called The Hour Glass Anthology and printed about one hundred copies myself. This process of getting so close to the words on the page taught me something about poetry that I hadn’t yet learned. To make a long story short, I scrapped this premature version of Glass City Blues and destroyed all the copies I made. (I think an old friend of mine still has a copy, which I fear he will unearth.)

After the destruction, I sat down to write a new poem. I called it “Glass City Blues” (which I had not yet used for a poem title). I sent it out, and it became my first published poem. I wrote a few more poems, some of which were published (one was in Literary Orphans), but after I graduated I became steeped in filmmaking, which led me to Los Angeles. Fast forward eight years and I’m studying fiction in my MFA Program at Antioch University Los Angeles. My wife, who is also an artist, became interested in poetry, which inspired me to revisit that craft. I hadn’t published any verse in years (though I had certainly tried). It seemed that my poetry had improved due to studying fiction so closely, and that I was hitting a new note. I liked what I was writing, so I sent the work out, much of which was published.

I noticed themes in the published work, mostly geographic themes. I compiled these poems into a manuscript, and the crystallized version of Glass City Blues was the result.

We understand that you like to explore style and convention when it comes to writing. What kinds of unique twists on formatting can we find in Glass City Blues? What are you trying to capture with these transformations?

Most of the work in Glass City Blues is free verse. It is only recently that I have been experimenting with more formal poems. For example, I am currently enthralled with forms such as the ghazal, the villanelle, and the sestina. Keep in mind that I studied fiction, not poetry, for two years during my MFA. I got to know poets there and attended poetry seminars; their love of poetry was contagious. This semester, I have been a teaching assistant at the University of Tampa, which has pushed me to think more formally about poetry. I’ve been thinking a lot about meter and stressed versus unstressed syllables. This thinking doesn’t really play into Glass City Blues (unless it happened subconsciously), though you may see it in my new poetry.

As far as formal twists, there is section in Glass City Blues compiled of visual poems. These visual poems are mixed-media collages. As I noted, my wife is an artist, and watching her paint inspired me to find my own way to express myself visually. I had always been inspired by the visual poems of Joel Lipman, a Toledo poet, d.a. levy, and others. The visual poems in Glass City Blues seek to break the boundary of formal verse on white space on a piece of paper; they incorporate maps, hand-painted illustrations, words stamped with ink, and are all arranged on pages from a biology textbook. These choices were all intentional and the result of experimenting with failed attempts for over a year. This section is called “How to Build a Heart” and I am trying to capture the feeling of displacement—within the body, within relationships, within a city.

That sounds beautiful! You mentioned that you felt your poetry improved after studying fiction and that pursuing an MFA in fiction helped you hit a new note. How so? What changed?

First of all, my first mentor, Alma Luz Villanueva, truly encouraged me, and probably all of her students, to work beyond the restraints of genre. Alma would guide me toward “la poesia” when I turned in my fiction for her to review. She had a massive reading list which included poetry, fiction, and non-fiction. Alma also writes across genres. While pushing me toward la poesia, she also emphasized the importance of dreaming—in a literal and figurative sense. I remember one time she told me to take my characters into a dream space. Following her advice, I went into the desert in Rancho Mirage and meditated while spiritually invoking my characters. It might sound untraditional, but I believe in loosening things up. Alma would often discuss her own practice, which seemed to sometimes include drafts of story ideas as poems, or poems as stories; only later would the true form of the work reveal itself. I had this experience a few times. Some of my poetry turned into fiction; some fiction turned into poetry. I think Alma’s perspective on life and writing certainly had an influence here.

Additionally, studying language deeply comes with the urge to pursue other mediums. In my opinion, much of writing works in concert with other genres. I can’t say that I know of any writers who exclude a medium from their reading repertoire. There may be a few who focus on one genre, but generally writers read widely and promiscuously. For me, working deeply within fiction naturally propelled me toward poetry because I was fueled by the desire to feast on language. I cannot say that I’ve had this experience with non-fiction. This may come some day, but for the last few years it has been predominately fiction and poetry.

Not only are you a writer, but you’re an actor and a filmmaker! You’ve even had a short film selected for Cannes Film Festival. That’s a huge deal. How does your filmmaking inform your writing?

Let me first say that I have not worked on films or acted since 2015. I put so much energy into filmmaking and acting for many years, and I came to a point when I realized that my true love was writing. Once accepted into the MFA Program at Antioch, I decided to focus solely on writing. However, filmmaking, screenwriting, and acting were a major part of my life. They are still a part of me, even though I am mostly concerned with fiction writing and poetry these days.

It is easier to think of this question in terms of my fiction writing; there are many ways the filmmaking and acting informs my work. Plot, character, story, dialogue, scene. Acting taught me to think more deeply about the characters I write—what is their motivation? Their desire? Who are they? Studying story structure in screenwriting embedded the natural flow of plot in my fiction writing (some of which had to be unlearned because fiction tends to be more about the internal nature of a character).

With poetry—it is hard to say. If anything, I would say that I had to deconstruct much of what I knew about filmmaking and acting in order to approach poetry more authentically. However, I can attest to performance as an influence on my poetry. As I noted, the poems in Glass City Blues are less formal. Perhaps performance provided me with the tools to write with a natural flow, and to write with my own voice. Acting, even though it is about becoming another character, still forces the performer to look within. Before acting, I can’t say that I had ever looked so deeply within myself. As my true voice began to flow, it seemed that more poems generated with a consistency of voice and tone.

Let’s talk about dreams. You’ve explored many creative ways to tell stories, share emotions, and explore moments both through the written word and visually. From page to screen, what would be your dream project?

Every time I read a novel I love, I think about adapting it for the screen. For example, I just read The Past is Never by Tiffany Quay Tyson, and as soon as I finished it I found myself mentally putting a developmental package together—who would star in it? Where would I begin the screenplay? Could I work with the author on this? However, when I catch myself doing this, I need to quickly stop. I do it with poems, also. There has been a trend in the past decade to adapt poetry for the screen, which is wonderful. However, the reality is that I must stay true to my own projects. It has taken me a long time to learn what I don’t want to do. As far as a dream project—that is tough to say. Adapting the work of Toni Morrison would be a dream. Adapting a piece by the poet Ai would also be a dream. An anthology television series of adapted poems—that would be just wow.

Can you tell us about a few artists who inspire you? What about them inspires you?

There are probably too many to name. There are, of course, writers with whom I have been so fortunate to study: Rane Arroyo, Tim Geiger, Kyle Minor, Jane Bradley, Alma Luz Villanueva, Gary Phillips, Alistair McCartney, Francesca Lia Block, Jim Krusoe, Peter Selgin, Donald Morrill, and others. The influence they had upon me was profound. Not a day goes by that I do not feel grateful for what these writers and artists taught me. Even though I am no longer a formal student of theirs, their work continues to inspire me; I learn from them daily.

What are you working on at the moment?

Right now I’m working on my first novel. However, I’m currently earning a Certificate in the Teaching of Creative Writing, which has put my writing slightly on hold. I’m able to write a little bit each week, but not as much as I would like. I’ve been working on this novel since approximately April of 2017. I also have a finished collection of short stories, which I have been sending out with my fingers crossed.

You’re very enriching to listen to, and we can’t help but admire the beautiful lens through which you look at the world. For our younger writers, is there any piece of advice you’ve learned that you wish was imparted to you when you were first starting out?

That’s quite nice to hear. I try to look at the world this way, but of course we all have our bad days. Lately, I’ve been journaling a lot and making the annotation “Positivity Day #17”, etc. to help alleviate a lot of the darkness I experience due to past traumas. For this, I say that writing can help to heal. The process of writing for the self, for the body, for the mind, for the soul—this has tremendous power.

Regarding craft and working toward publishable work—my advice is to keep writing. To paraphrase Anne Lamott: Write shitty first drafts. Don’t be too consumed with success while you’re young. Even now, turning thirty this year, I am probably rather young to be considering writing as seriously as I do. Writing quality material takes experience. It takes life. It takes loss. Growth. Pain. Strength. Endurance. Perseverance. Dedication. Fool-heartedness. I might also advise that if you can do anything other than writing, you probably should. At least while you’re young. Put experience under your belt so that you have something to write about later. If you just have to write, and find that you’re compelled no matter what, then read widely. Read as much as possible. The classics, modern work, and contemporary. Let literature teach you. Learn grammar so that you may write clearly and eloquently; you want control of your words. You may consider pursuing an education in English and writing but this is not necessary. A library card, used books from a thrift store, and the Internet will serve you well (though use the Internet sparingly and only as a way to learn more about the history of literature so that you can check out the best books from the library). Don’t always read what everyone else is reading. Write as much as possible, that is to say often—not necessarily quantity. Finally, learn to love revision. Revise, revise, revise. See the work again (truly re-VISION). Don’t send your work out until you’ve revised it enough times, had space from it, and are willing to live with it should it be published. I have made the mistake of hurting people I love with my writing and now I can never take it back.

Thank you for taking the time to talk with us! We greatly appreciate it. Where can we pick up a copy of Glass City Blues?

Directly from the publisher:

https://www.finishinglinepress.com/product/glass-city-blues-poems-by-nathan-elias/

From Amazon:

https://www.amazon.com/Glass-City-Blues-Nathan-Elias/dp/1635346916/

From Barnes and Noble:

https://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/glass-city-blues-nathan-elias/latest Nike Sneakers | Yeezy Boost 350 Trainers