My mother was stuffed to the gills with excuses the day she called to confirm that, yes, she and my father—both approaching 90—would be moving, at least for the summer and fall months, from their spacious, two-bedroom condo overlooking Sarasota Bay, Florida, to a small house in Yellow Springs, Ohio, permanent population three thousand. They’d considered Chicago where I reside but had knocked it off the list because it was “too big” and “too expensive.” Since when was money an issue? My parents were loaded.

I pictured my mother wearing a sleeveless cotton nightgown with faded flowers, standing in the kitchen, neatly writing the day’s “To Do” list (Number One: Call Jane and tell her we are not moving anywhere near her)—script

that must have won her As in penmanship and an extra dime rolled into her weekly allowance.

My mother was no dummy. She had a well-rehearsed explanation for why my parents had decided to bale. Living in a senior citizen high-rise community, she said, was like staring mortality in the face. “One day a neighbor is waltzing down the hallway; the next, she’s being pushed in a wheelchair and slobbering all over herself. Or maybe we never see her again and find out in the condo newspaper that she has passed away.”

She had me there. It was impossible to walk anywhere in the Sarasota Bay Club without dodging a wheelchair being pushed by either a health care worker or a spouse who looked one fall away from landing up in a wheelchair himself.

So, when my sister found the house in Yellow Springs, my parents grabbed the get-out-of-jail card and headed up north. Apparently my sister wanted to take full responsibility and all the credit for my parents’ move. What I took was a load of guilt.

I’m the oldest daughter. It was my assigned role to care for my parents in their old age. But I never made the offer. Figured they’d live to a hundred and then die an honorable death at home in their sleep. But my sister, unmarried and, as she never failed to remind me, a volunteer hospice worker, donned a Zen robe and decided to make up for all the years she and my mother had battled over just about everything because, I would guess if I’d been asked (and I was not), that my mother was jealous of the close relationship my father and sister shared. Funny, because growing up, I felt that my sister was in competition with me for that honor.

But we didn’t talk much about feelings in our family. It was as if we were in the ring for what we anticipated would be a knock down, dragged out boxing match and had all retreated to our separate corners. A referee didn’t blow a whistle to urge us back into battle. A manager didn’t patch our wounds and tell us how important it was to finish what we’d started. There were no winners. No champions. No trash talking. Just a family afraid to ruffle feathers.

A month after my parents moved to Ohio, my sister called to ask if I would please come and stay with them while she and a friend went camping. She was exhausted, she said, and needed some “space.” My father had been a “real pain”—surprising, because up until the MOVE, it had been a love fest between those two. But the balance of power had changed. “He’s not the same. He doesn’t like the furniture I’ve bought, the way I’ve arranged the house, the way I pay the bills.”

I suggested that he might feel emasculated.

“What?”

My sister’s vocabulary was never her strong suit.

“You know, the guy no longer wearing the pants.”

My sister started to cry. Maybe I’d been too harsh. She’d taken on something I couldn’t or wouldn’t. “Look, I’ll clear my schedule.”

The white clapboard house on Winter Street sported forest green shutters, a red front door, and a small front porch—a blurry-eyed vision of some drunk’s idea of Christmas. It was ordinary, not much different from its neighbors up and down the block. So, this is the “adorable” house my mother fell for? Nothing about it was adorable, certainly not the scraggly, untended excuse for a garden next to the red, uneven bricks that constituted a driveway of sorts. And I hadn’t even been inside. My parents had traded in their lofty high-rise condo for this small, unremarkable, on-the-verge rundown place. I wondered if the bed and breakfast around the corner had a room.

My dad was at the side door when I pulled my car into the driveway. I barely had time to turn off the ignition before he launched into his woes. “Listen, I want to talk to you before you go inside.”

Now what? I‘d only just arrived.

“Things aren’t going well with your mother.”

“What’s wrong?” I said, already wishing that I hadn’t come. My sister wanted my parents close by. She should have stuck around to handle this.

“It’s just so hard to see her like this.”

“What’s ‘like this’ mean?”

My dad choked on his words. “She’s not herself. Her memory is shot.”

“It must be hard for you,” I said, trying to mirror his feelings when I really wanted to ask him why he was spending every day on the golf course instead of with my mother.

“I can’t take it anymore. It’s wearing me out.”

He looked like a battered old man who’d lost his best friend. And he had. I couldn’t imagine what he was feeling. He’d always said that he wanted to die first. But he didn’t get to call the shots. None of us does.

The bags under his eyes drooped halfway down his face. His hair, still fairly full, scattered every which way: clearly, he hadn’t used a comb when he woke up that morning.

My father wrangled my suitcase out of the back seat and rolled it up to the stairs before lifting it and carrying it into the vestibule.

Whatever respite I had hoped to bring to my parents (and my sister) evaporated like the water in an outdoor fountain on a hot, muggy August afternoon. My sister barked from across the room: “Take off your shoes. I’ve worked hard to keep these floors clean.”

I untied my black tennis shoes with the white rims and placed them squarely on the vestibule rug.

“Am I allowed to enter now?”

“Yes.”

I curtsied and, with a flourish, waltzed into the living room.

My mother hadn’t moved from her chair or given any hint that she was upset about my sister’s commands. In the past, she’d have stepped in immediately with a “Now, girls.” But things had changed; she didn’t seem to notice.

A large print book was open and propped on her lap.

“What are you reading, mom?” I nuzzled my head against hers and kissed her gently on the top of her head.

“Oh, just some book.”

The woman who’d organized book clubs and often led the discussion now couldn’t even remember the title.

“Is it good?”

“Oh, you know. Nothing special.”

My mother hadn’t let on that her memory was on life support. When we spoke on the phone, she asked me a host of questions but never talked much, if at all, about herself. She was crafty enough to try to hide her forgetfulness. And she’d succeeded. She’d bamboozled me into thinking that she was still on her game just like my brother had convinced us all that any thoughts of suicide were long gone. He took his own life on his thirtieth birthday.

I walked over to the windowsill and picked a dead leaf off of one of the plants.

“Stop it.”

My sister again.

“It was dead.”

“That’s my job, not yours.”

“Oh, and I can’t pick a dead leaf?”

“No.”

“For God’s sake, what’s eating you?”

“Nothing. It’s just that I work so hard to keep this house up. I don’t want you or anyone else stepping in.”

She’d taken yet another step toward a breakdown.

“Strange because you had no problem asking me to come down and bail you out.”

There, I’d given her a “what for.”

“You were always so bossy—the older sister. And you haven’t changed a bit.”

“Me, bossy? Are you kidding? ‘Don’t pick the dead flowers.’ ‘Take your shoes off.’ You’ve been dishing out commands since the minute I arrived.”

My father slowly rose from the wicker chair. “That’s enough.” He looked at my mother sitting immobile with the book opened to the same page. “We’ve got enough problems.”

Yeah, right. I couldn’t wait for the fun to begin.

My sister disappeared and, within minutes, reappeared with a backpack slung over her shoulder. She practically sprinted out the front door without more than “Be back on Monday.”

I heard her car rev up and than rumble backward down the brick driveway.

I was shocked when, later in the evening, my mother suggested that the three of us play a game of Scrabble. I glanced at my dad, trying to gauge his reaction. In years past, our family often sat at the dining room table and enjoyed a good game of Scrabble or a couple rounds of Word Duel. My mother was almost always the winner and usually racked up double the points of her nearest competitor. But now she had trouble doing simple things like following a recipe, completing a crossword puzzle for beginners, or following a conversation. I couldn’t count on her for much of anything.

“Well, are you two ready to play?” my mother said. She’d made her way to the small table with the Scrabble game in hand.

Again, I looked at my father who hadn’t budged from the wicker chair. I thought of our conversation earlier in the day and wanted to encourage him. “C’mon, dad,” I said, grabbing his hand and pulling him up from the chair. “Let’s play Scrabble.”

He resisted but was too weak to overpower my tug. I felt like a mother yanking her screaming two-year-old out of Walmart.

We joined my mother at the small oak table with one of its leaves folded flat against the south kitchen wall. I sat at the rounded end that jutted out into the kitchen with my mother seated to my right and my father to my left. I was in the middle again. My mother shook the maroon velvet bag that held all the tiles, and then, one by one, each of us reached into the pouch and took the prerequisite seven letters.

While I pondered my first word, my mother dropped several of her word tiles on the floor.

“Shirley!” my dad said. “Quit dropping the tiles.”

“Oh, Mor. What’s the big deal?”

“They’ll fall into the heating vent. That’s the big deal.”

I hated my dad for being so damn insensitive. Each time she dropped a tile, I shot him a nasty look, bent down, and picked it up. None of them ever got close to the vent.

My mother was having trouble making a word. I looked at her letters and saw at least two obvious possibilities. I resisted helping her because I thought she’d be humiliated.

“Shirley,” my dad said in that accusative voice of his. “You’re taking too much time.”

She looked at him and glared. All I could do was shake my head in disgust and wonder how my parents had stayed together for sixty-eight years.

My mother continued to stare at her letter tiles. At one point, she picked up a letter and started to place it on the board. I held my breath. “No,” she mumbled, realizing in that split second that she’d forgotten whatever word had filtered in and then out of her mind.

“Shirley,” my dad said again. “You’re taking too much time!”

That did it. My mother threw down her tiles, shoved her chair from the table, said something about “Play your own damn game,” and marched into her bedroom, slamming the door behind her.

I sat, my arms folded in front of me, fuming. “You’re a mean man.”

He flinched but, instead of hollering, asked me to please go talk to my mother and bring her back to the table.

“That’s your job, not mine,” I said, trying to keep my voice down so my mother wouldn’t hear.

“I just can’t stand to see her this way.”

I didn’t give a damn about his feelings. He’d become a stranger to me.

“Please, Jane,” he said. “Go get you mother.”

I knew my going wouldn’t solve a thing.

My dad put his severely sun damaged hand covered by red and purple blotches and small, open sores on top of mine. The blotches disgusted me.

“I’m asking you to go get your mother.”

Yeah, and will you add money to my inheritance?

I pulled my hand from under his and placed it ceremoniously on my lap.

My dad had removed his glasses. The deep indentation from the nose clips on either side of his long, prominent nose and the dark, puffy shadows under his once blue but now milky eyes made him look like the old man he was. Despite myself, I felt sorry for him. Sorry for him, for my mom, and for me. Our family was falling apart, disintegrating in front of my eyes.

“I’m doing this for me,” I said, getting up from the table, pushing the chair away.

I opened the door and found my mother standing at the end of the bed. She’d taken off her robe and was wearing the same cotton, sleeveless nightgown with faded flowers. I couldn’t tell by looking at her face whether she even recalled what had just transpired.

“I am so proud of you, mom. Most people who have memory problems would never dare to suggest playing Scrabble. But you’re a trooper.”

I nestled my head in between her large breasts and felt safe, protected. The irony of my feeling secure when my mother was so helpless was not lost on me.

“Why don’t you come back to the table?” I said, reaching for her hand and leading her back to the kitchen.

She shuffled in front of me, taking small, uncertain steps.

My dad managed a faint smile. “Glad you’re back.”

I bet you are. I saved your ass.

I pulled my mother’s chair out and, still holding her hand, placed her body squarely in front of the chair before having her sit down.

“Now where were we?” she said.

This was the last game of Scrabble the three of us played. My parents died less than a year later only three weeks apart. Fittingly, my mother died first and carved a trail for my father to follow: he would have been lost without her.

Jane Leder is an author and blogger. The 2nd edition of her award-winning book, Dead Serious, a book about teen suicide, is available online and in hundreds of libraries across the country. Her other books include Thanks For The Memories: Love, Sex, and World War II and Brothers&Sisters: How They Shape Our Lives. Leder’s blog, seventynme.com, focuses on the joys, challenges, and issues most important to women 70+ (though she welcomes younger subscribers, too.) You can check out her website at janeleder.net.

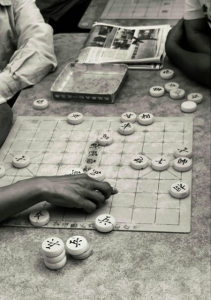

–Art byJ. F. Chow — Artist Profile