An Interview with T Kira Madden

Growing up, I wasn’t an introvert, but I spent most days with my nose buried between the spines of books. Sure, watching cartoons on Saturday mornings helped me explore my imagination and even make friends, but never quite the way reading did. Writer, photographer and New York transplant, T Kira Madden feels similarly. Born in Miami Beach, Florida, Madden spent much of her life “hanging out with Encyclopedia Brown, and The Boxcar Children and Harriet the Spy.” She chanted the works of Edgar Allen Poe and attended magic classes religiously. And through that magic, she found art and an alter-ego named Vesper.

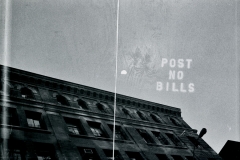

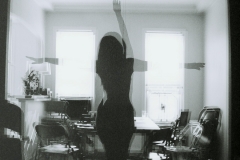

Madden began writing first, coming up with “stories about pirates and bologna sandwiches on my grandma’s electric typewriter.” That love eventually blossomed into experimentation with photography. The uniqueness of her work is bold and striking—yet the images are welcoming and familiar. Using film only, Madden stresses negatives with scratches, heat, and even other images, before taking pictures.

Despite having a background in visual art and fashion design from Parsons School of Design, getting an MFA in writing from Sarah Lawrence was where Madden found her heart. “I met some of the greatest people I will ever meet there. I learned how much I hate the workshop experience but also learned about the goodness of human beings. I really don’t have a vocabulary large enough to express all my love for that little gnome village.” Madden now teaches writing with three different programs—including a jail—where she helps “people find out what it is they want to say;” she helps them capture their thoughts and ideas into whatever images they wish to cultivate. With photography, Madden is able to do just that by playing with her work. I spoke with her last month.

The Fiddleback: You teach writing at jail. What’s that like? How long have you been doing it and what made you want to? How is it different or similar to teaching at Gotham Writer’s Workshop?

T Kira Madden: I taught at Valhalla Correctional Facility for two years. Now I teach in a homeless shelter up in Harlem—a program called The Doe Fund (and I’m still at Gotham, yes). But whether I’m teaching homeless men or incarcerated women or adults just looking for something more, it’s really all the same. It’s about helping people find out what it is they want to say. And all three of those groups have so much to say. Sure, the environments are different. Sometimes I’m surrounded by security guards and sometimes I’m eating cupcakes in a classroom, but it really comes down to the conversation and the laughs. I cannot say I teach anybody anything—they’re all smarter than me, believe me. I’m just there to tell people who have been told to shut up all their lives, “No, talk.”

The Fiddleback: Who is Vesper T. Woods?

TKM: Vesper was always a way for me to stay outside myself. In graduate school, my dear friend and teacher David Hollander once said to me, “I read your writing, and I see none of you in it. You are a gentle person but your characters are so violently cruel (he was probably more eloquent than that,”) and I remember thinking this was the best compliment I could ever receive. I would like my own blood to be nowhere found in my writing.

Vesper T. Woods had no history, no gender, no agenda, no real meaning or personality or phobias, and so it was the exact non-identity through which I could enter a truly blank page. Since then I have found it a braver task to remove that psychological crutch. I’m just using Peter Sellers as my spirit animal guide.

The Fiddleback: Being both a writer and a photographer, is there a medium that you prefer?

TKM: No. The process is too similar for me. I wouldn’t have one without the other. I couldn’t.

The Fiddleback: Would you say your work has a distinct style or theme? What would you categorize it as?

TKM: I would like to think of both my photography and writing as good portraiture. But you would have to ask someone experiencing it. Themes are not for me.

The Fiddleback: You photography is unique in that the image produced is intentionally blemished. What inspired you to stress the negatives the way that you do? What kind of materials do you use to do so?

TKM: Curiosity, I suppose. The play of it. All I want in a portrait is for it to represent the person to the best of my ability. And people are blemished. People are gorgeous and crooked. So I look at a person and I stretch, bend, burn, tape, bleach their film—I buy half my film to shoot, the other half to expire—anything you can think of, I’ve tried it. Recently I carved my own face with a needle. I’ve also been playing with Polaroid development using water and ink. It’s like squishing around an old oil sticker.

I respect digital photography, absolutely, but I’m not interested in using it. I’m not interested in that kind of precision.

The Fiddleback: Can you talk a little bit about each of the images? What are the stories behind them? What have they been stressed with?

TKM: Some of this selection is nothing but good old expired film. I’m talking maybe seven years expired. The others are double-exposures and reflections. I like using glass and mirrors very much—but I won’t say how. Photographs are like magic tricks, why would I tell anyone how it’s done? Photos and stories would be nothing without their magic.

I hope someone finds his or her own stories in these without my ruining it. I won’t write the placard for you. All I will say is that here you will see a portrait of Evan Rehill, a portrait of Stephanie Malove, a portrait of Annabel Graham, a portrait of 8th Street, a portrait of Yumna Al-Arashi, and a portrait of Jana Krumholtz. I am happy with their accuracy.

The Fiddleback: Is there a difference in capturing an image through a photographic lens versus capturing an image through writing?

TKM: They are both about getting a person right. And they should both have some kind of story, some sort of swoop to them. I suppose there is more pressure with landing a portrait because you are trying to nail the human being in front of you, not the voices in your head. I can tell the voices in my head, “Shut up, I’m still trying to figure you out,” or “I’m going to give you a scar across your face today and see what happens,” but I can’t say that to a friend, usually in the nude, posing for me. I only have so much time with them, and it’s important that I make them feel comfortable. I can torture my characters all I want.

The Fiddleback: Your work consists mainly of film photography. What made you chose film over digital (besides tampering with the negatives)?

TKM: I only shoot film. I began shooting at around age 12 and it was an old film Canon and I learned to trust its weight and its ticks and the way I could measure light and smell a film canister. I learned to wait for results. My hands only know this kind of camera body now. I respect digital photography, absolutely, but I’m not interested in using it. I’m not interested in that kind of precision.

The Fiddleback: Our culture seems to be moving away from different forms of technological advances and going back to more tangible things—gramophones, film, typewriters, even—why do you think that is? Is it a love for something vintage, or is it grittier than that?

TKM: This is a tough question for me because I never really moved on from those things. I never moved on from my childhood typewriters—I have eighteen of them by now. I still have a landline plugged into a rotary phone; I still crank a pencil sharp. I come from the Evan Rehill school of Romance Activism, of keeping these things alive. But it’s exciting that these objects are “cool” now—why shouldn’t they be? They are beautiful and breakable. I will embrace technology without Luddite snobbery, but I will also continue to wind my pocket watch. Maybe other people are just craving that balance.

The Fiddleback: Because artists try to capture the perfect image, do you think it’s possible to do so even if the mediums are purposefully distorted? Is it even possible to capture the perfect image?

TKM: I think it completely depends on intention. Aesthetically, yes, I have seen perfect images. Watch a Hitchcock film and try to tell me he doesn’t knock you over the skull with perfect composition. Filmmakers usually land that aesthetic perfection for me.

For my own work, again, I want the perfect representation of a person rather than a perfect photograph. I remember the first time I watched Annie Hall, the scene in which Alvy and Annie are speaking to one another but the subtitles are scrolling with their true thoughts. I thought, why shouldn’t photography do this? How can I get the physical person and the inner-other-self in one photo? This is why I only shoot people I know well. This is also why I mostly use double-exposures. If I could get twelve frames in one like Étienne-Jules Marey I might be more accurate, but I do my best with two to four. When I get the whole person, I am pleased.

The Fiddleback: Is there anything new that you’re working on?

TKM: I’ve only been working on stories with my photographs in them, so that’s a new form for me—punctuating written moments with little images. It’s a different type of role playing and it’s thrilling; I take a photo based on what my characters would shoot or notice. Then I have this funny, strange mess of the photos informing the words, the words informing the photos, back and forth and so forth.

I’m also dreaming up a literary journal right now called No Tokens. I have the best team of female powercats and one high-haired male wizard working with me, and I think we’re about to make some eyes rattle.

——–

T Kira Madden