An Interview with T. J. Proechel

by Benjamin Davis Brockman

by Benjamin Davis Brockman

February 1, 2012

From 2008 to 2009, Photographer T.J. Proechel worked as an real estate owned contractor at the height of home foreclosure crisis in his native Minnesota. After graduating with a degree in Photography from Baltimore’s Institute College of Art, Proechel found jobs difficult to come by in the Twin Cities. Little did he know that his time in real estate would a creative vantage point on a what would become the very face of the new recession.

Proechel’s ongoing series, Dream House, depicts the sobering truths of foreclosures without being overtly political or casting personal agendas on his subjects. The imagery is immediately tragic, humorous and clever—acting as a unique form of documentary. Proechel’s eye catches the nuances of the stories of real people in difficult times without using the individuals as subjects. His work begs many questions about the nature of the documentary in photographs, and the process of creative discovery.

I spoke with Proechel in the winter of 2011.

The Fiddleback: Many of your photographs have an austere, peaceful quality to them. How do you decide on an aesthetic approach in portraying such a complex social subject?

T.J. Proechel: This project wasn’t pre-conceived. It really grew out of what I was doing and seeing on a daily basis. I don’t ever remember thinking about the kind of images I wanted to make. There were certain motifs that kept reoccurring though: beds, distressed rooms, homes at night, etc. I did my best not to make it overly sentimental. When I was making this work, there wasn’t a lot of other pictures of the foreclosure crisis to look at. I was just making pictures, making images that were compelling, which related to my experience. At that time I was in a pretty dark period of my life—partly because I was working in these depressing foreclosed homes. I think that bleeds through into the pictures a bit. Although I didn’t really think of it as a project, until I’d been making images for a long time, making these images was, at the time, the only thing I was excited about. In retrospect, it is the only thing that validates what would otherwise have been a wasted year.

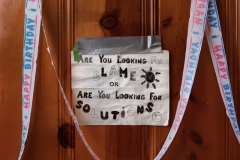

The Fiddleback: How does humor enter into your work? Is it something you look for?

TJP: I’m a big fan of humor. I hope the images I was making weren’t overly ironic. In photography, irony is often the only way humor is expressed, which I find mind-numbingly boring. This is partly because it has been so over used and partly because it’s so directed and its meaning can be so closed. I’m far more interested in a photography that is ambiguous and one who’s meaning isn’t right on the surface.

The work I’m making now is more open, and there’s not a ton of humor in it. On the other hand, humor can be a great entrance point for a lot of people. It can be a very affective way to draw people in and then get them to deal with the other issues I’m trying to bring to bear.

The Fiddleback: Can you talk about working with the homeowners that you met? What was their attitude toward being documented?

TJP: Well, in many ways I don’t think I could have made this project in any other place than Minnesota. My position within this project is a bit of a precarious one. Although I was working on the project and outside of it, I was also ultimately hired by the banks to take care of these houses after the homeowners left. The reason I think this project was different in Minnesota is because Minnesota deals far differently than most states with people who have been foreclosed on. By the time I meet anyone who I photographed they would have known for nine months that they were going to have to move out of their house. So more often than not, people were resigned to it.

The Fiddleback Would you describe your creative process as an act of discovery? Do you set out with certain things you really want to find or depict or do things occur to you as you work?

TJP: Photographing out in the world is always an act of discovery. I don’t really make lists of things I want to photograph, but I do always have in my head photographs that I want to make. Most of those things don’t ever get made, but I always have them there, and they inform the actual pictures I make.

I never intended to make this project. I didn’t even imagine myself to be making a project. I was just photographing the things that were around me.

The Fiddleback: The title of this series is Dream House. How did you come to choose this title? Did this inform your aesthetic?

TJP: Well, Dream Housewas, and is, a working title. I don’t really remember coming up with it, but it kinda just stuck. I really don’t like the title actually. It’s a bit too tongue-in-cheek. In a way, I feel like it makes light of a situation, which doesn’t deserve that sort of flippant lightness. It’s stuck on there for now, but eventually I’ll change it.

The Fiddleback: There is certain ethereality to your images, some of which is inherent in the spaces as you find them. How deliberate are those metaphorical connections?

TJP: I’m not sure that I would describe the project as ethereal. There’s a certain eerie quality or creepiness, which is often inherent in just being in these spaces. But there are certain images within the project, where I’m trying to make reference to larger cultural structures that created the foreclosure crisis. I may be the only one who can see those references, but those images are important to me. Even if those things aren’t readily on the surface, I think it creates a tone for the project.

The Fiddleback: How do you feel about this quote from Robert Polidori: “My belief is that you should take stills of what doesn’t seem to move, and take movies or videos of [what] does.”

TJP: To be honest, I don’t think much of Polidori. I think his work is Google street view with a large format camera. I think you only need to look at Edgerton’s work to know how bunk that Polidori quote is. To my mind there’s nothing that doesn’t move. Everything is in constant motion. I think the basic roll of photography is to stop motion and point towards what’s important. He seems to have no discernment of what’s interesting and what’s not. And it’s not in a kind of Egglestonian democratic forest kinda way, which points to the everyday and asks us to meditate on it. Polidori is interested primarily in the exotic and foreign, but renders them indistinguishable from one to the next. He’s an incessant photographer, but after looking at his work I never feel like I’ve learned anything new. His work seems to be invested in reinforcing prevailing narratives.

Although thinking of it in that context peeks my interest a little bit. I could read an essay about the relationship between Google street view and Polidori and be convinced, but his work doesn’t move my meter even a little bit. He does make pretty pictures though; that does make me slightly jealous.

The Fiddleback: What are your interests in the documentary, either in film or photo journalism? What do you see as the role of the documentarian? Does he or she have certain responsibilities?

TJP: That’s a huge question. I believe the documentarian does and doesn’t have certain responsibilities. It’s important to note here that historically and presently the majority of documentary work is done about poor, most often third world brown-skinned people. This obsession with the disenfranchised and poor is ingrained within ideology of photojournalism/photo documentary. Paul Graham’s American Night deals exceptionally with this issue.

This history is vast, but hasn’t changed much since Jacob Riis made his photographs that are collected as “How the Other Half Lives.” In these images, Riis photographed the slums of New York and, most famously, young children who worked in textile plants. The difference between Riis and most modern photo documentarians is that Riis advocated for something specific. He advocated for “model tenements” and child labor laws. His work was specific and directed and had a tangible affect on the people he depicted.

Contemporary photojournalism is completely different. Unlike Jacob Riis, who lived in the community he photographed, almost all photojournalists (including Robert Polidori and Andrew Moore) drop into a region, spend two weeks there making pictures and then return home with a project. There is no activist or personal engagement with the subject. Although those two things are not requirements for making compelling and engaged work, what results from that way of working are tried and cliché images, which don’t bring to light anything new about the subject, but rather reinforce the given and present narrative. This is a problem that affects all of journalism and not photojournalism specifically. I would say that the type of documentary I try to make is done in the first person. Meaning that I’m interested in making a project that I’m directly affected by. When making the foreclosure project, it wasn’t a matter of finding a “hot” topic and then making a project about it. I never intended to make this project. I didn’t even imagine myself to be making a project. I was just photographing the things that were around me.

This is, of course, not the only way to make documentary projects, but I think it’s important to work towards a photojournalism, which is more open and doesn’t impose directed and preconceived narratives on a subject. This has happened in ways, but there’s a long way to go.

The Fiddleback: What are you influences? What art, music, or films drive you?

TJP: I like lots of things. But in this moment I’m most interested in Hennessey Youngman, Kanye West, Jay-Z, Joel Sternfeld, Taryn Simon, Pierre Huyghe, Judd Apatow, Allen Iverson, Gunter Grass, Ernest Hemingway, David Foster Wallace, Andy Kaufman, Eddie Murphy (Delirious), Louis C.K., Ted Sorensen, Sonic Youth, Paul Graham, Mike Tyson, Oliver Chanarin and Adam Bloomberg.

The Fiddleback: An earlier project featured on your website is about Baltimore. What connections, if any, are there between these two series? Each piece seems to have a very specific story. What is your interest in those personal stories? Are you more interested in the general social phenomena you address?

TJP: Baltimore is a scary city. I lived there for four years, and although for the most part I avoided getting fucked up, I knew a lot of people who weren’t so lucky. I started doing that project after a taxi driver was shot outside of my apartment building. I lived right next to the Remington neighborhood at the time, which was one of the most violent neighborhoods in the city. Neighborhoods in Baltimore are very different than most cities; they are very small, often only five or six blocks.

For this project I photographed all the places murders had taken place in my neighborhood, while I lived in that apartment. I collected all the text from police reports then went to the sites. I did the project to help myself conceptualize the neighborhood I was living in, but the pictures have been generously called memorials, which I liked to think that they are in some small way.

The Fiddleback:How does the advent of digital technology and social media affect your methods? In photography, is this liberating or a detriment to medium?

TJP: It’s both. I’m a young enough photographer to have always had my work on the Internet. But the biggest thing I feel that it’s doing is forcing me to make photographs that are more legible for the web. This means making them very directed and stripped down. These less visual and conceptual images work far better on the Internet.

The Fiddleback: Who is Adam Burroughs?

TJP: “Adam Burroughs does not exist.” He is a con artist who swindled me out of money, while I was renovating a house for him and several investors.

The Fiddleback: Can you talk a little bit about what your doing now? Is this project ongoing? I read that you were doing some traveling between Saint Paul and Los Angeles.

TJP: I’m currently tracking down Adam Burroughs. I did my first trip last May and will do another this summer. I’m waiting to finish the project before I put any of it up on my website.

——–

T.J. Proechel