The Rebirth of Slick: Shabazz Palaces Live

It’s Record Store Day and I have lined up in the wee hours outside of Other Music near the Bowery to buy a rare vinyl recording of a live session from Shabazz Palaces. This elusive, experimental new hip-hop duo from Seattle stunned the indie music community last year with Black Up, their debut LP from Sub Pop: a rap revelation of truly lyrical lyrics that runs atop a filthy chassis of brutish, sodden sub-bass. Twenty-something music hipsters instantly gobbled it up, acclaiming the group’s sound as entirely new. But, as the saying goes, everything old is new again.

When I get inside the store, I’m hoping to grab one of only 2,000 copies of Shabazz Palaces’ new 12-inch, “Live at KEXP”—a provocative little number, on grape soda colored vinyl, featuring the duo’s full studio performance at Seattle’s legendary KEXP radio station. And apparently, I will have some competition at the crates. Behind me, a guy in his forties also has it on his shopping list, and he is happy to tell me how he glad he is to have found new, “mannered” hip-hop that doesn’t make him feel inappropriate when he’s rapping along. In front of me, a gaggle of pale-faced, paunchy college boys is talking excitedly about how “Shabazz Palaces is amaaazing.” “Yeah,” one says, “They’re kind of like Odd Future and Death Grips, but better for some reason.”

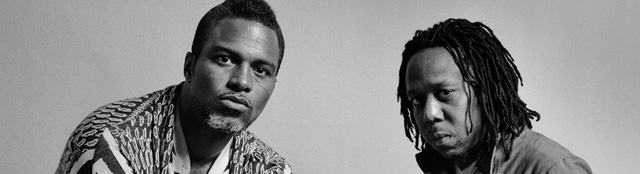

That reason may have something to do with the fact that Shabazz Palaces’ members were pressing wax when the youngbloods in Odd Future were still eating crayons. The group’s frontman, Palaceer Lazaro, is better known to older listeners as “Butterfly,” the founding member of another genre-expanding hip hop group, Digable Planets. DP’s 1993 release, Reachin’ (A New Refutation of Time and Space), was a platinum crossover hit that took “intellectual hip hop” to a new level with its sampled pedigree of Miles Davis, Art Blakely, and The Last Poets. Palaceer Lazaro, née Ishmael Butler, looks a little like a Last Poet himself these days—he turns 40 this year and sports a graying goatee, but his alluring, Afrofuturist brand of funky hard bop rap has lost none of its vitality from when he pioneered it twenty years ago.

The other half of Shabazz Palaces is Tendai “Baba” Meraire, age 38, a classically trained percussionist who produced his first album at the age of 12 and comes from a family of world-renowned Zimbabwean musicians. With that heritage, Baba brings a thousand years of African musical tradition to bear upon Black Up:he plays several different percussive instruments on the album, some that were only first introduced to the U.S. in the 70’s. The resulting texture is authoritative and grounded—and infinitely appealing to an audience craving authenticity in the age of commercial rap.

The virtuoso caliber of the duo was evident the moment they took the stage this past spring at SOB’s in Tribeca, as part of their first tour. There was no grand mic-snatching entrance; Palaceer Lazaro and Baba, clad in retro leather jackets and aviators, quietly tinkered with their instruments like violinists tuning for concert pitch—Lazaro at his laptop and SP-555 Sampler, and Baba with his snare, floor tom, and two congas wrapped in a kente cloth. Then suddenly a dirty reverb beat dropped and the two launched into a choreographed shoulder shake routine à la Motown legend Cholly Atkins.

From the opener, “Youlogy,” with its catnip hook (“Caked up and faked up to get you HIGH”), Lazaro began to cantillate rather than spit his denunciations of thug culture and media hegemony in a maple syrup alto, and a hundred other music reviewers in the room, self included, swooned. Recalling Richard Roundtree with his bourbon-colored silk scarf and mesomorph build, Lazaro brandished his trademark blend of liberation poetry and cosmonaut grooviness (“Old school hood nigga, press and curl / Eyes like moons when I kiss my girl / Get lucked out, wish I was in Africa”). A friend turned to me and said, “I bet that guy gets mad pussy.” As if in answer, Lazaro rhymed, “I gleam and glow, I’m clean / And oh you bet ya that I get it bro.” We were not the only ones caught up: when Lazaro arrived at his refrain, “Black is you, black is me, black is us, black is free,” raising his fist in the Black Power Salute, I caught one white guy reciprocating and thought I saw another, but it turned out to be a guy just holding up his iPhone at the wrong moment. Meanwhile on stage, Baba Meraire, short of stature but long of braid, worried the snare, tampered with the congas here and there, and provided backup vocals, seeming content to pose as the modest sidekick.

Then the mbira came out, and everything changed.

Baba’s role in Shabazz Palaces cuts far deeper than a nice little live percussion accompaniment to the superfly Lazaro. It is my belief that Tendai Maraire could even be more responsible for the Shabazz sound than Ishmael Butler. In the 1970s, Baba’s father, master drummer Dumisani Maraire, introduced the mbira instrument to the U.S. This small finger piano, the size of a paperback book, is a sacred instrument of the Shona people of Zimbabwe. When placed inside of a deze, a halved calabash gourd that functions as a resonator, the mbira’s delicate windchime sound is amplified to an otherworldly, ethereal effect, and is used in Shona religious rites to communicate with the spirit world. There is a short mbira interlude on “an echo from the hosts that profess infinitum,” the eeriest track on the Black Up album. The song features a heavy blown-out bass layered under a chilling chant that sounds like a chorus of crying ghost children—something is definitely being laid down for the spirit world. However, in live performances, Baba draws the interlude out for several minutes and the result is nothing short of mystical. To listen is to be transported to the high plateau above the Limpopo valley, into a tropical all-night ritual under a gallery of stars.

Much critical attention has been paid to how opaque Palaceer Lazaro’s lyrics can be; his syntactic abstraction is both mysterious and frustrating to listeners, but Lazaro remains reticent when asked to comment on his meaning in interviews. When placed in the context of Shona tradition, however, Lazaro’s stream-of-consciousness makes much more sense as a sort of spiritual summoning. The rap returns to a musical element—verbal percussion—that serves Meraire’s instrumentation, instead of vice versa. In rhymes like “Play it then, let my soul unwind / Streams of energy now intertwined,” there is a shamanistic endeavor: a desire to tap into another consciousness to achieve a transcendent, truthful experience. Many lyrics refer to a performative undertaking: “I can’t explain it with words / I have to do it,” and, perhaps the catchiest chorus on the album, “It’s a feeling.” Viewed in this light, it is clear that Lazaro is rejoining with the true genesis of freestyle rap: spontaneous, innate expression.

When Cuban pop arrived in Africa in the 1950’s, it sounded both exotic and familiar to African listeners and was embraced unequivocally, then reappropriated into Afropop. Likewise, the enthusiasm for Shabazz Palaces may indicate that they are re-Africanizing hip-hop. For young audiences, this is a revelation, a coup de foudre on the scale of what Native Tongues supplied for Generation X, and what Black Star and the Soulquarians delivered at the end of the millennium. Many “millennial” listeners, however, haven’t yet discovered those elders, even as their favorite artists from the new underground—OFWGKTA, Wiz Khalifa, Big K.R.I.T.—sample heavily from their predecessors.

Once inside Other Music, I do end up jostling at the record crate next to one of the tadpole Pitchforkcores who stood in front of me in the line outside. To my surprise, he turns from the crate and hands me the second-to-last copy of the Shabazz Palaces release before grabbing his own. With an endearing, very genuine smile, he says, “This’ll be the album of the summer!” I thank him and walk away thinking, it’ll last longer than that, young buck.

——–

E. E. Lyons