Flight

nonfiction by Lori Litchman

Tired from a day of working to bring the kitchen of our century-old Philadelphia twin into at least the twentieth century, my husband Dave and I are lugging broken-down cardboard boxes to his car so he can take them to be recycled. The air is heavy and moist on this dark August night when a ship-sized, maroon Chevy Caprice comes barreling down our narrow street, careening toward us. For a moment, I am scared. And then I’m not. It’s just John.

John is an African-American man in his fifties, who, except for his missing incisor, looks like he’s barely pushing forty. When we first moved to this street nearly five years ago, he was renting the home across from us and was quite welcoming, always chatting about his life and his opinions on everything. He’s a mechanic and is usually wearing his navy work overalls, always topped off with a thick gold chain, a solid gold boxing glove dangling at the focal point of his neck.

John parks his car behind ours and the three of us talk about random things, from what it’s like to skin a deer, to kayaking, to the neighborhood. John has been in prison, for what he won’t say, and he’s been addicted to crack, which he freely admits.

“Ya know, I wanted to buy that house next to yours,” John says as he takes out some rolling paper and begins rolling a joint. Dave and I both refrain from telling him that a developer bought it yesterday to fix it up with the intention of selling it. We instead tell him that it doesn’t have any floors and needs too much work. John sits on the front of his car and starts toking away, not asking us if we want any. He knows we don’t. John makes a little extra money selling pot, and we’ve watched him sell it right in front of us to passing drivers.

“I used to sell when I lived across the street from y’all,” he says, “but you’d never know it.” He then goes on to explain to us how stupid it is to sell drugs in front of your home, because it attracts the police. We listen to his urban wisdom, nod and smile. We like talking to John, and we’re pretty sure he likes talking to us.

“I was just plannin’ on going to get some milk and smoke a J and then I ran into y’all,” John says. “You got me talkin’ here for like thirty minutes or something. Dag.When are we going kay-yaking?” he asks.

One of the last conversations we had with John was when we were loading our kayaks onto our car for an afternoon on the Schuylkill River. He rolled up in his usual car, a black Mercury hatchback, and hopped out in the middle of the street to shout, “I thought yous all were just some boring-ass white people. I didn’t know you went kay-yaking!” In that moment, we were ‘cool’ in John’s eyes.

After he finishes smoking his joint he says he has to go, shakes Dave’s hand, and gives him a chest bump.

“Stay black,” John says to Dave.

What do you say to that?

“You too,” Dave replies.

Old Growth Forest: A forest that has lived numerous years. It usually contains large trees, both living and dead, young and old, and has a wide variety of trees. A diverse array of animals call this forest home. Once humans disturb, it can take a century to several millennia to completely heal.

Second Growth Forest: A forest that has regrown after a disturbance, typically one caused by humans. Contains limited biodiversity. Takes anywhere from 40 to 100 years under the best of circumstances for a second growth forest to start looking like an old growth forest, although many fail to recover.

What we didn’t tell John was that for quite some time, we have been thinking about leaving this neighborhood and that our actions directly led to the sale of the house next door. Let me explain. Dave and I had discussed at length whether we should move. After a shooting in front of our home that left bullet shells littered in front of our fence, after some local teens threw a skateboard under Dave’s bike in an attempt to launch him into traffic, after a derelict neighbor stole Dave’s Social Security number and identity and after numerous racial incidents, he was finally starting to agree with me that we should think about moving. We decided that we’d contact a realtor friend and neighbor of ours to see how we could go about putting our house on the market and move to a more stable, thriving community.

Chris, our realtor friend, used to live on the block directly behind ours, but sold his house to move two blocks north – a veritable world away from his former home. Philadelphia is what you call a ‘block-by-block’ town, meaning that you can have a quiet family block right next to a block with rampant drug activity. Chris moved to the family block to get away from the drug block. Our street is in the middle of those two and has both families and drugs.

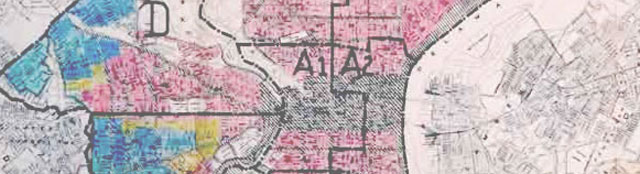

Our neighborhood is right on the border between Germantown and Mount Airy. Depending on whom you ask, our block can be considered part of either neighborhood. Realtors consider it Mount Airy. We consider it Germantown. Here’s the difference: Historically, Mount Airy has been hailed as one of the best-integrated neighborhoods in the country, even by Oprah Winfrey. Neighborhood lore says that when whites began fleeing Philadelphia en masse in the 1950’s and 60’s, residents of Mount Airy started going door to door, convincing their neighbors to stay and learn to live together with their new African American neighbors. It worked. Mount Airy remained a stable middle-class neighborhood. But times have changed in the last ten years, increased property values in Mount Airy have made it upper middle class and upper class, and unaffordable for us when we were looking to buy. The reason that we moved to our street in Germantown was because it was the closest home to Mount Airy that we could afford.

Coincidentally, Dave ran in to Chris in the neighborhood a few weeks before our conversation with John. Dave explained that we were thinking of selling our house when I finished graduate school, but there was one major obstacle – the house attached to ours had been abandoned for the four years we’ve lived in our house, and we suspected it would be difficult to sell a home attached to a floorless, gutted twin. Chris said he hadn’t realized that it hadn’t been fixed up and that he should come by and look at it. Chris, who had recently started a partnership to buy and flip houses, was quick to come peruse the dilapidated house and within weeks had bought the shell for $25,000. We were ecstatic for several reasons. First, we could actually think about selling our house when we were financially able to do so, and second, it would be one less abandoned house on our block. Construction began swiftly and we were happy to hear the whir of saws and the thud of hammering next door on a daily basis.

Then, within days, something else happened in our neighborhood that we couldn’t have predicted. The abandoned house across the street from us, the house that I lovingly refer to as the ‘Psycho House,’ due to its resemblance to Norman Bates’ screen home, started getting a makeover. Twenty-foot-high weeds had taken over the front yard of the Psycho House, which had broken windows, cracked stucco, and a see-through roof. Neighborhood children would throw stones at the house when they walked by on their way to and from school. Invasive English Ivy had taken over the right side of the house, hiding some of the pock-marked exterior. The Psycho House exuded blight.

It was late August ’08 when the men showed up, tools in hand, to tackle the weeds. I was pretty certain that they would cut the weeds and then leave. I had filed countless reports – sometimes daily, sometimes weekly – with the city’s Licenses and Inspections department, complaining about all of the following: high grass and/or weeds (I think 20-foot high bamboo counted), vermin (feral cats had staked their claim in the house along with a hunchback raccoon), imminent danger of collapse (the right side always seemed to lean a little too much), and trash (people had taken to using the front and back yard of the house as a dumping ground). The men began their attack on the yard with a weed whacker and soon upgraded to a sawzall and then a chainsaw to cut the weeds. And then the men were gone, toppled weeds strewn lifeless across the property.

But they came back the next day and then the next. When the backhoe showed up to clear the front yard, I had to stop myself from doing a jig on the street. Instead, I sat on my front porch and watched as the yellow monster cleared all the debris, literally scooping up pounds of trash, along with bamboo and sumac entrails. The men then got to work on the façade of the house, laying creamy stucco on every square inch. They added brand new windows and got started on the roof.

But then one day in late 2008 they stopped coming. And the American economy started collapsing. And the house remained untouched for three years.

In the meantime, Dave and I rehabilitated our outdated kitchen, removing our metal sink cabinet and sink, adding a countertop, new stove, and a dishwasher. Also, we were impressed with the work the contractors did building a porch next door, so we hired them to demolish our sagging porch and build us one to match our other half. The porch and the kitchen were the only major projects that needed finishing. Other than minor cosmetic updates, the house could realistically go on the market any time.

And while we are happy to see all of these changes happening in our neighborhood, we feel partially guilty about the gentrification. While the community is looking better than it has in decades, what happens when people who have lived here for those decades start to get pushed out because they can’t afford to pay their taxes any longer? But, our desire to flee this neighborhood and get out is incredibly strong, and it competes with the guilt we feel for being able to leave this neighborhood willingly, and either rent or buy in a much more desirable neighborhood. And we are aware that if we put our house on the market we can get more for it than we paid, even with the economy in shambles. We can put our money in our pockets and walk away to a better place. We also know that we are not in control of the neighborhood and that gentrification would have happened had we never moved here. Given my neighborhood’s close proximity to a much more desirable one, the transformation couldn’t be avoided. Our flight from our home wouldn’t make a difference at this point. At least that’s what we make ourselves believe.

Habitat Fragmentation: When a habitat that was at one time continuous becomes divided into pieces. The pieces often become isolated from one another. Fragmentation is often a result of human destruction.

Philadelphia, like many great American cities, has a history of movement and flight, the most significant period being after the end of the World War II. After the war, there was a critical housing shortage due to the deteriorating condition of most homes, the majority of which were built in the 19th century. African Americans also began migrating North to escape the South’s lack of political rights and freedoms, the social problems of segregation, and the economic problems associated with a lack of job opportunities. My current neighborhood, Germantown, was hit particularly hard when people and jobs left the city for the suburbs. Germantown was one of those neighborhoods where so-called “white flight” altered the neighborhood forever.

Philadelphia at large suffered, too. In 1950, the city’s overall population was two million. But by 1960, Philadelphia had lost its place as the third largest city in the country to Los Angeles. By the 2000 census, Philadelphia’s population was 1.5 million, a net loss of one-fifth of its population from 1940. Early gentrification changed the dynamic of several neighborhoods in the heart of the city— today considered some of the wealthiest parts— including Society Hill, Rittenhouse Square, and Queen Village. The latest statistics available show Philadelphia in fifth place in the country, behind New York, L.A., Chicago, and Houston.

But, the trend looks like it could be reversing. In 2005, National Geographic Traveler named Philadelphia America’s Next Great City, citing recent revitalization efforts and its charming cityscape, particularly the downtown area. The city has seen a pattern of baby boomers moving back into the city, because they’ve already raised their children and need not worry about Philadelphia’s deficient public education system. And, more and more young urban professionals are staying in the city instead of moving out to the suburbs. Gentrification has already happened part and parcel throughout most of the neighborhoods bordering the downtown area, and it has steadily crept out of the city center to areas like mine.

And now there are projections regarding the growth of cities that predict that the massive influx of people back into cities across the country is going to turn the suburbs into the next slums. At a recent Society of Environmental Journalists conference I attended, ‘smart growth’ experts discussed how people are now looking for walkable communities, where they can live and shop in harmony. Philadelphia is a prime location for such endeavors, because it is such a walkable, bikable city. The consequences of this estimated flight will affect poor, mostly African American people in Philadelphia, who will likely be pushed out into the far suburbs where they’ll have fewer job opportunities and greater economic stress. In fact, at this conference I attended, the environmental reporter for The Philadelphia Inquirer, Sandy Bauers, asked the presenters about the potential for mass gentrification in somewhere like Philadelphia, envisioning bulldozers coming into impoverished areas of the city to make way for Smart Growth revitalization. The presenters said it was inevitable, that it was already happening in areas throughout the country, and that the entire transition would likely take about 20 years.

Edge Effect: A transition area between two ecological groups. The boundary area provides habitat common to both groups and often contains greater diversity than either of the individual areas. Although still up for debate, many ecologists see the edge effect as harmful to the organisms who live in the fragments of each environment.

When I moved to my neighborhood, I was really just looking for a nice place to live, where I could have a small yard to plant a garden and have some space for my future dog to play. Apparently, that’s exactly how gentrification starts, according to sociologist and professor Elijah Anderson, author of Streetwise: Race, Class, and Change in an Urban Community. Dave and I are living textbook gentrification and are in fact, what Anderson calls ‘urban pioneers.’ We live in the ‘edge,’ an area where two communities collide, where there is a mixture of middle class white people and low-income blacks in the same area. Anderson says friends and family often question these urban pioneers at length about the safety of their neighborhood and repeatedly encourage the urban pioneers to move. We don’t speak of our experiences to our immediate family because we don’t want them to worry, and many of our friends who live outside our neighborhood can’t understand why anyone would want to live here. In fact, our friends love hearing our neighborhood “stories” whenever we attend dinner parties. They sit and listen entranced, wondering how we put up with the antics in our neighborhood. Often, Anderson says, the urban pioneers make it for only about a year, and decide to leave after encountering certain unpleasantries, such as vandalism or racial tension. We’ve made it through seven years here, and are likely to stay at least one more.

Those who move to what Anderson calls the ‘shadow of the ghetto’ are usually attracted to affordable homes built in the architecture of times past, the promise of a yard and/or garden, and the ability to have an area to keep pets. But once the area becomes desirable to other middle-class people, white or black, the property values begin to soar, as do the taxes. Anderson writes: “The trail of gentrification appears self-sustaining, destined to continue as long as there is a supply of housing. The past successes of the developers, recent activity, and the prospects of high profits from the renovation of still more homes will help fuel future development. Once the process begins in earnest, its continuation appears inevitable. But the change initiated by developers and young urban professionals will not come quickly or easily. It will be a slow and arduous struggle, at times almost imperceptible and at other times very evident.”

Change is inevitable.

Anderson also says that often these urban pioneers retreat into their homes and if they can’t overcome the feeling of being under attack, they will cash in on their investment and leave. Others, though, are slowly won over by the special quality of the neighborhood. Some of these urban pioneers forge strong friendships with other urban pioneers, because they are all essentially going through the same thing. This description is our life. We do feel like we are often under attack and have formed friendships with all of our middle-class neighbors to discuss ways to improve the community, including our new neighbors who live in the spruced-up house attached to ours. But we aren’t sure whether we can stay much longer. And we’re even less sure that we should leave.

Migration: The movement of one population of animals from one place to another. Migration is usually seasonal and done in response to changes in food and/or temperature.

When I think of migration, I think of the phenomenon of birds. Birds have an internal clock that tells them when it’s the right time to take flight. The availability of food and the weather in their current environment are major indicators as to when to leave for a warmer climate. Birds tend to set out on their journey when they have a strong tailwind, to make the trip easier on them. But, once they get going, little will stop them, as they pause only periodically to refuel for the flight. If a bird makes a mistake, though, like waiting too long to leave, it could be disastrous. It could be left without food or get caught in weather that could lead to death. If we humans, too, are not able to receive the nourishment we need from our environment, isn’t it only natural that we flee to an area that will feed us?

I left my small, rural-Pennsylvania hometown because I knew it could no longer sustain me intellectually. I also knew that there would be little opportunity for me to find a job with a college degree there. I migrated to Philadelphia to feed my brain and nourish my soul. But, I feel like the struggle of living in my neighborhood is slowly starving me, and if I don’t leave, it will slowly drain every ounce of my spirit. I’ve worked too hard to let that happen, and I feel ashamed by the fact that I want to live surrounded by other people like me: educated, law-abiding, and open-minded. I’m tired of fighting to help this second-growth forest of a neighborhood survive. I need an environment where I can thrive and live freely without worrying about what could happen to me each time I step out my door.

Not too long ago, Dave was biking home from work when, just a few blocks from our home, he passed three young African-American males walking on the sidewalk. Two of them bent down to pick something up and within seconds, Dave felt the weight of a rock smashing into his head. Always the teacher, he hopped off his bike to confront the teens and hopefully try to teach them a lesson. He told them to take him home to their parents so he could tell them what they had done to him. They laughed at him. He screamed, “You think just because I’m white you can throw a rock at my head?” hoping that an adult would come out and shame these boys. There was no response from any of the homes on the street, while another group of young, black males began approaching. One teen approached him and had the following exchange of words.

Young male: “What, you wanna rumble?”

Dave: “No. I just want a little respect.”

Young male: “I don’t need to respect you ‘cause you white.”

Dave: “That’s a completely racist thing to say. Think about what Barack Obama would say if he heard you talking like that.”

Young male: “Barack Obama don’t care about you ‘cause you white.”

Dave: “We’re never going to live a peaceful life if people are racist like you.”

Young male: “Why don’t you go back to West Chester where you came from?”

Dave, pedaling away: “You guys need to grow up.”

This incident was not the first incidence of racial tension we’ve experienced in this neighborhood, and I doubt it will be the last. It makes us frustrated and suspicious of young black males, even though we fight against having these racist thoughts. But, Dave and I think these issues are broader than race. There are also issues of class, poverty, and education. We both have friends who are African American (some of whom have told us they would never live in our neighborhood), we both willingly choose to live in what we thought was a well-integrated area, and as teachers by trade, we have both spent years of our lives educating minority youth when we both could have easily chosen to work in a wealthy suburb. We aren’t racist. Yet. But we worry that if we continue to live in this neighborhood, that we will become racist no matter how hard we try to fight it.

The damage has already been done to this former old growth forest of a neighborhood, and I don’t know that it can ever recover from the ills that plague this second growth forest. As long as I live here, I will continue to help this community grow in any way I can muster the energy to do. But, in order for a full recovery, everyone has to do something to improve the neighborhood – our environment. Unfortunately, given our experiences, I see marginal growth among further fragmentation. Unless my husband and I can feel completely safe and nourished here, we’ll be looking to take flight to an old growth forest ripe with diversity, stability, and opportunity where we will put down new roots.

——–

Lori Litchman