An Interview with George Boorujy

by Jeff Simpson

December 1, 2010

George Boorujy works on a scale and at a level of detail that is impossible to take in at once. The size of his paintings—they can be as large as six feet high by ten feet wide—combined with millions of brushstrokes is simply astounding.

Boorujy’s work follows in the tradition of nineteenth-century naturalist John James Audubon, whose groundbreaking book The Birds of America—published as a series between 1827 and 1838—is still considered a masterpiece of book art and one of the finest ornithological works ever completed. Like Audubon, Boorujy seeks to represent the natural world in painstaking detail, but where Audubon sought to paint and catalog as many North American birds as possible, Boorujy is thematic, creating subjects that are at once hyperrealistic in detail and dreamlike in presentation. His animal portraits—painted in ink on paper and set against stark, white backgrounds—look back, reminding us that we, too, are animals and still share our environment no matter much we as a species have changed the ecological strata. What makes Boorujy standout as an artist is his willingness to undercut his sense of realism and painstaking brushwork with tones of the surreal—a smudge of smoke wafting through an otherwise negative backdrop, an animal’s gaze or posture that feels unnaturally human.

A marine biology student turned artist, Boorujy received his BFA from the University of Miami in 1996 and an MFA from the School of Visual Arts in New York in 2002. He was named a fellow for the Smack Mellon Artist Program in 2009 and a New York Foundation for the Arts Fellow in 2010. When I reached out to Boorujy, I asked about his methods, his general views on art, and his attraction to North American animals and landscapes.

The Fiddleback: There’s an obvious connection to the natural world in your work, but what I find most interesting are the surrealistic qualities–missing elements in the landscape, sterile backgrounds that house animal portraits in startling detail. How conscious are you of using negative space to push against realism? Would you say one of your goals is to break the photorealism we’ve come to expect when viewing representations of the natural world?

George Boorujy: The negative space is almost as important–maybe AS important–as what I actually draw. Making these images is like distillation. I try to whittle down the image to its essential parts, only including what is absolutely necessary. It’s also a way to focus the lens on what IS important in an image. If there’s all the grass and sky and pebbles making up the background, foreground, etc… then nothing has any more importance than anything else. This way, every rock or twig that I decide to include is there for a reason, there’s no extraneous stuff in there. The viewer is really visually sophisticated, so I’m not ever worried about confusing someone. If it’s a little disorienting, that’s fine. That’s what I try to do with the compositions in general – there’s enough for the viewer to grab onto, yet hopefully it’s a little “off” so that they have to slightly readjust their normal viewing pathways. If it was set up with a sky and clouds and all that, it fits too easily into what we’re used to seeing all the time. And then maybe people won’t look as astutely. As far as breaking photorealism, well, I never really got the point of most photorealism. It’s sort of like Madame Tussades or something, like, “Look how we made it look JUST like the picture!” Yes, I do get the conceptual “why,” and I’m being dismissive, but yeah, just making something look like a photo always begs the question, “Why not just show the photo?” That was a really long-winded way of saying, “Yes. The negative space is important.”

The Fiddleback: The gaze has always been an important fixture in portraiture (or all art for that matter). Given most of your portraits involve naturally shy animals looking directly at the viewer, how does direct visual contact alter our preconceptions of these subjects?

GB: I think what I’m after here is interaction rather than pure observation. I want the viewer to relate to these subjects rather than just look at them. Also it’s again a way to “re-see” things that we’re used to seeing. We’ve all seen a million paintings of deer or horses, or bluebirds, but if you take those familiar animals and present them in an unfamiliar way, it forces you to have to REALLY look at them. There’s something primal and thrilling when you make eye contact with a wild animal–even if it is just a deer–and I want to remind people of that. It’s something pre-language.

The Fiddleback: Violence seems to be a recurring theme in your work. Are you simply interested in portraying nature in all its beauty and brutishness or is there something deeper at play?

GB: Hmmm, I’m going to get all sorts of semantic and say that it depends on how you define “violence.” I don’t think of the images as containing all that much violence. I think of it more as an exploration of the reality of things around us. There is life and death all over the place, constantly, but we prefer to look the other way, cover it up, choose to only show certain aspects of animals and ourselves. I’m close to running the risk of getting very (and embarrassingly) philosophical about this, but there is an endless exchange of life and death in the world. We think of something like a wolf living off of the death of other animals, and we can get all “Lion King” and “Circle of Life” and about that, but the same is true for a barn swallow or a jellyfish. These animals are as carnivorous as a wolf. All life in the sea, for example, is based on killing. No vegetarians in the ocean. Except maybe manatees.

The Fiddleback: Do you have different goals in mind when drawing humans rather than animals?

GB: Not really. The strangest question I get from people is, “So why are you so interested in Nature?”, as though we are separate from Nature. We ARE Nature. With a big N. I’m a large social primate that lives in an enormous colony (New York) situated on a very productive estuary. We are all functioning within a certain ecosystem, no matter how much we change it. Hell, beavers do the same thing. We’re just better. Or worse depending on your point of view.

Ink on paper is totally unforgiving, so everything has to be planned before I start. If I screw up I have to start all over. But I like that that reinforces the ideas of decision and restraint in the work.

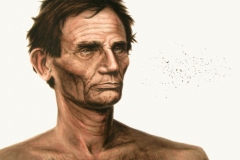

The Fiddleback: What was the inspiration behind the Lincoln portrait?

GB: I had just done the portrait of the deer. The idea being taking a familiar animal and presenting it in an unfamiliar way. I had Lincoln on the mind for some reason. I think what fascinated me was the fact that he was a person who lived not that long ago, but had achieved a status of beyond human. An icon. And I mean that in the real way, not like, “music icon, Robert Plant.” But he too, was a living, breathing, human man. I had thought about doing a full body, but I think it would have crossed into a cheap sensationalistic realm with people just focusing on his nuts. I decided to cut him off at above the nipple to avoid any of that. But I wanted to show his physicality–the awkwardness of it too–and also wanted to strip away the familiar beard. Again, the idea of taking something so familiar, but making you have to see it anew.

The Fiddleback: In our age of interactive media, one could describe using inks as a very analog method of creation. What’s the advantage of working with ink rather than Photoshop or oil paint or charcoal?

GB: The only way I could be doing something simpler would be if I was crushing berries and smearing them on a rock. I actually use Photoshop a ton though to plan out compositions, try out colors, etc… Ink on paper is totally unforgiving, so everything has to be planned before I start. If I screw up I have to start all over. But I like that that reinforces the ideas of decision and restraint in the work. I also like working on paper because it somehow takes itself less seriously than oil paint. Also seems to let the viewer in better. Something about the simplicity of the materials.

The Fiddleback: What kind of paper do you use?

GB: Since some of the pieces are quite large I need to get a big roll. Other than that, I just use what seems nice. I’m using a Fabriano paper that I really like at the moment.

The Fiddleback: How long does it typically take to complete a drawing from concept to finished piece?

GB: That’s a hard one. The ideas incubate for ages. The actual final stage of making the piece doesn’t take too long, but the planning can take a really long time. I’ll work on more than one piece at a time typically. A big piece (four by eight feet or so) will take about a month to make once I have figured out the majority of the composition.

The Fiddleback: Do you travel for research?

GB: I don’t know if I travel expressly for research, but everywhere I go ends up being inspiring. With the exception of the California desert. I go there on purpose.

The Fiddleback: What’s the state of the contemporary art world? Are there enough avenues for young, under-represented artists?

GB: It’s hard. Really hard. But hasn’t it always been? Except maybe for a brief window in the ‘80’s. I think there’s a lot of good work being made though. So that’s good. There needs to be more focus on getting younger people to start collecting. Some people will think nothing of dropping a couple thousand on a new couch or something, but they balk at buying art for some reason. Or don’t think of it. I also think that there needs to be more affordable art shown with more established artists. Gallery owners should take some risks on emerging (cheaper) artists. And then encourage those without huge bank accounts to get out and collect. As far as the non-commercial world, the funding is down for a lot of organizations. Which makes competition for grants tighter, and the rewards less. It’s incredibly difficult and any artist has to balance scrambling for the next dime and actually making work. Unless of course, you’re independently wealthy. And there’s a long tradition of those artists. Hard not to have a chip on the shoulder about that, but damn I’d love to be in that club.

The Fiddleback: Did you enjoy working on our fiddleback logo? (I still can’t believe you drew it on the cheap before we even had a website.)

GB: Very much so! Even if I did get it to you terribly late.

——–

George Boorujy